Rough Trade earned its reputation as an indie imprint with left-leaning ethics and a post-punk sound. But when a Manchester band called the Smiths signed to the label in 1983, all that was about to change.

Excerpted from Rough Trade: Labels Unlimited by Rob Young © copyright 2006 Black Dog Publishing Limited. Adapted and reprinted with permission of the publisher.

In 1976, Geoff Travis opened Rough Trade as a record shop in Notting Hill, a London neighborhood that, at that time, was heavily populated by Caribbean immigrants. Consequently, the shop did a brisk business in reggae and dub while also stocking the underground punk that was about to explode in popularity with the Sex Pistols’ 1977 debut. A believer in the co-operative business model, Travis was not a typical boss. All the shop’s employees received the same wage, and all took part in regular meetings that turned into discussions about the relative musical and ideological value of records.

Travis and his staff would hang out, blasting reggae and punk singles from their huge sound system and playing host to shop visitors such as the Ramones and Patti Smith. Travis’ crew conducted enthusiastic detective work in tracking down obscure records that no one else bothered to get: Iggy Pop bootlegs, the first Talking Heads singles and masses of reggae and dub imports. By 1977, Rough Trade was acting as a distributor, and by 1978, it had evolved into a record label thanks to some assistance (in the form of a £4,000 loan) from Travis’ father, an insurance assessor. (Today, the shop and label both thrive as separate entities, having amicably split in 1983.)

In the beginning, Rough Trade struck deals with artists based on a 50/50 split of profits, and the label operated out of a shed in the record shop’s backyard. Early releases included singles by sonic collagists Cabaret Voltaire, punk rockers Stiff Little Fingers and dub artist Augustus Pablo, but Rough Trade later earned its reputation on the “scratchy-collapsy” sound of post-punk: Scritti Politti, the Raincoats, Subway Sect, Pere Ubu and the Fall.

Rough Trade’s collective-minded, politically correct culture quickly earned it the stereotype of a “loony leftie” label, its employees crunching on brown rice as they discussed which international oppressed workers’ groups should receive a charitable donation from the company profits. While Rough Trade’s ethical considerations made it a model for countless indie labels that followed, not everyone was happy with the house rules. One such artist was Mark E. Smith of the Fall, which was signed in 1980.

“They had a whole meeting over the fact that we mentioned guns in one song,” Smith told journalist David Cavanagh. “And I’d go, ‘What the fuck has it got to do with you? Just fuckin’ sell the fuckin’ record, you fuckin’ hippie.’”

Rough Trade’s non-hierarchical, non-management style, which had made its early years such a hippie-ish idyll, soon became inadequate for the label’s swelling roster and mounting financial obligations. Travis was forced to focus his efforts on searching for an act that would make a viable bid on the national charts.

The Fall, which enjoyed Rough Trade’s best critical success, was becoming too truculent with Travis personally and refused to play the kind of compromising games that would take the band to that level. So Travis looked to Scritti Politti (whose “Asylums In Jerusalem” narrowly missed getting on Top Of The Pops in 1982) and a new signing, jangly Scottish guitar group Aztec Camera. Led by a James Dean-handsome singer named Roddy Frame, Aztec Camera was Travis’ great white hope as 1982 gave way to 1983. But at the end of such a turbulent year, he had no idea that his salvation was close at hand. In December 1982, in a tiny, cheap Manchester studio called Drone, a quartet of young men in their early twenties cut a demo of two songs, “A Matter Of Opinion” and “Handsome Devil.” Those songs, which would find their way into Travis’ hands within a couple of months, were credited to two songwriters, one named Morrissey, the other named Marr.

Money Changes Everything: 1983-86

“I tremble at the power we have, that’s how I feel about the Smiths. It’s there and it’s going to happen… What we want to achieve can be achieved on Rough Trade. Obviously we wouldn’t say no to Warners, but Rough Trade can do, too” —Morrissey, Sounds magazine, 1983

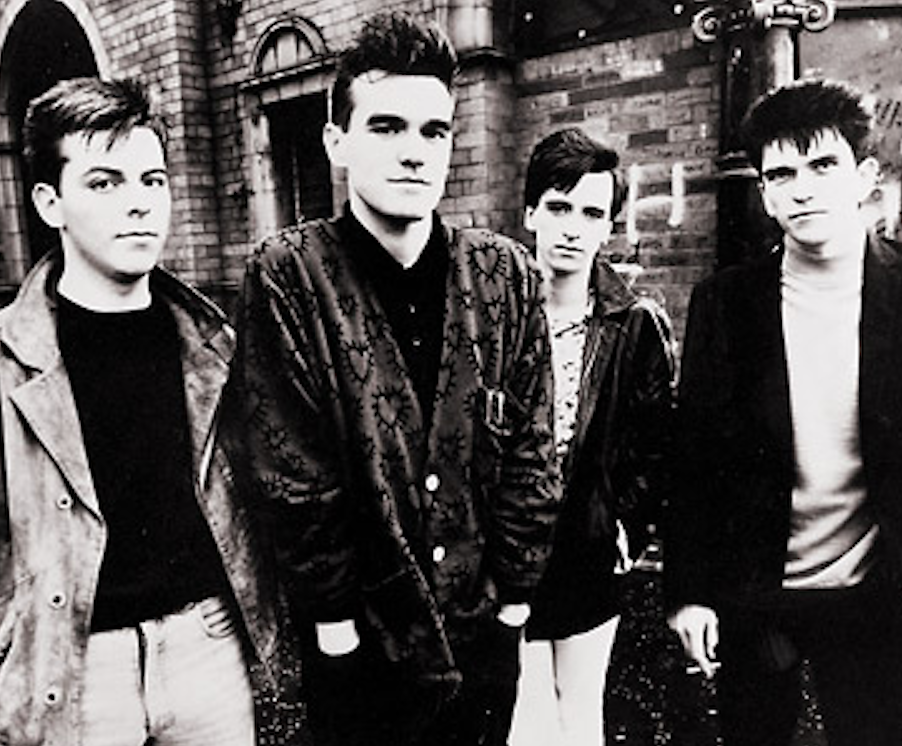

John Martin Maher was 15 when he met the reclusive Steven Patrick Morrissey, who was known as the singer and lyricist in a short-lived Manchester group called the Nosebleeds. The encounter, at a Patti Smith gig in 1979, lasted barely longer than a handshake, but Morrissey had made enough of an impression for Maher to seek him out three years later, when, as a guitarist and songwriter, he had developed grand ambitions to forge a British, post-punk equivalent of the writing partnership Leiber & Stoller. Like the legend of Jerry Leiber turning up on Mike Stoller’s doorstep with a proposal to work together, Maher beat a path to Morrissey’s house, chaperoned by a mutual friend. The chemistry was clearly right. Morrissey, who had tried and failed to become a music journalist and produced two fanboy pamphlets on his heroes James Dean and the New York Dolls, dropped his first name almost immediately following that meeting; Maher became Johnny Marr (avoiding confusion with Buzzcocks drummer John Maher); and the name the Smiths was selected by Morrissey not long after.

By the end of 1982, they had written a handful of songs, recorded two demo sessions and settled upon their definitive rhythm section, Andy Rourke (bass) and Mike Joyce (drums). Within three months, the Smiths would have their first record deal. Within a year and a half, they would achieve a U.K. top-10 hit. And within four and a half years, they would have split up, with five albums behind them. Their initial success was due to Rough Trade’s enthusiasm, but by the end of their run they would have tested the limits of what the company was capable of, transforming it in the process.

The hits Rough Trade had bargained on with a series of Scritti Politti singles had not transpired. And it was hits that Geoff Travis now wanted. The critical acclaim garnered by singles from the Go-Betweens, Virgin Prunes, Television Personalities, Konk and Aztec Camera had not translated into the kind of sales needed to propel them into the charts or onto radio playlists.

“When our first album went into the charts (Stiff Little Fingers’ Inflammable Material), we were very excited about that,” says Travis. “So we were quickly seduced by the idea. I think you want things that you think are great to be heard.”

Travis was certainly seduced by the Smiths. On March 23, 1983, he accepted the band’s invitation to see its first London gig at the Rock Garden.

“I see Morrissey onstage as pretty much a revelation at the Rock Garden,” recalls Travis. “Because he was fully formed. Dancing about, it was great. Then again, I remember some people were going, ‘I’m not sure about this lot.’ But you have to have that kind of ridiculous belief. If you take a consensus of opinion, you’ve had it. You end up signing Shed Seven.”

When Marr and Rourke pushed open the doors of Rough Trade’s London offices in April 1983, they were kept waiting for several hours to meet an overworked Travis. They finally buttonholed him in the kitchen and pressed the tape into his hand with an exhortation to treat it as more than just another demo. He lived with the two songs—”Hand In Glove” and a live version of “Handsome Devil”—over the weekend. By Monday, Travis was phoning Marr in Manchester and inviting him back to London the next day. The quartet leapt onto a train on Tuesday morning and, with Morrissey meeting Travis for the first time, agreed on a trial one-single deal. In fact, the group had already been turned down by several labels and had collectively decided not to sign to the iconic local label Factory. The Smiths felt Factory’s strong visual identity and association with a particular strain of Northern post-punk (Joy Division, A Certain Ratio, et al) would distort the public’s reception of their own sound.

“Hand In Glove” never breached the national U.K. charts, but it did sell well for 18 months after its May 1983 release. At one point the following year, it occupied the number-two slot in the independent charts between subsequent Smiths singles “What Difference Does It Make?” and “This Charming Man.” The track’s sheer emotional awkwardness—a veneer of public arrogance faintly masking deep inner turmoil and sexual confusion—sums up many of Morrissey’s later lyrical concerns, and its punching beat and acrid harmonica punctuation made it a live favorite.

Two sessions for BBC Radio 1’s David Jensen and John Peel in the summer of 1983 substantially boosted the Smiths’ fan base, which in turn gave Travis the confidence to commission further singles and an album. A third Jensen session in August sparked a media furor when the song “Reel Around The Fountain” was banned due to the BBC interpreting Morrissey’s lyrics (“It’s time the tale was told/Of how you took a child and made him old”) as a reference to pedophilia.

The producer of that session, John Porter, had heard the 14 tracks the group had already recorded for its album with producer Troy Tate, a former member of the Teardrop Explodes. Porter alerted Travis to what he considered the poor quality of Tate’s production and offered to take on the job himself. Tate’s version—available as a rare bootleg—has a roughness that would have placed the Smiths more firmly in the lineage of Rough Trade’s earlier lo-fi pop, while Porter cleaned up the sound and gave it a sharper edge. Travis and Morrissey agreed that Porter’s higher definition and multi-tracked guitars should become the signature sound unveiled on 1984 debut LP The Smiths.

The Smiths gave Travis a renewed vigor and a taste for popular recognition that he hadn’t experienced before. Rough Trade’s former short-term deals with its artists now looked like one-night stands, while the Smiths were its first serious relationship.

“They were our first long-term signing, our first serious commitment to making a commercial project work,” says Travis. “And to see how far we could take somebody, as opposed to just putting out a record. There was a different mindset. We were going to commit all our resources to the Smiths, and we wanted to have some kind of security. We don’t often think like that; we would still make stupid one-off deals all the time. But it just seemed obvious that this was a pretty special thing.”

Like most serious relationships, this one involved an inordinate amount of friction and communication between the various parties. Throughout their career, one of the Smiths’ biggest unresolved problems was the lack of a permanent manager they could rely on to handle the day-to-day running of a group.

“I don’t think they ever found that perfect manager who was able to balance [Morrissey and Marr] together,” says Travis. “Which is part of their tragedy, really. Had they done that, they would have probably lasted.”

For much of the Smiths’ peak period, they were effectively their own managers. Marr would often talk to lawyers and accountants, and he even booked taxis and tour vans. Meanwhile, Morrissey would take obsessive interest in the record artwork, coordinated with Rough Trade employee Jo Slee.

“Morrissey would do everything, talk to us almost every day,” recalls Travis. “Morrissey was awake in the daytime and Johnny was awake at night. For a record label, it was a dream, because they were so fully formed, and they knew what they wanted to do, and they were so fast. If they had a John Peel session to do on Tuesday, they’d write four songs over the weekend. They saw it very much in the same way that a working person would see it: That’s their job. It’s a wonderful attitude.”

Without a strong manager, there was no one to mediate the intra-band dispute that flared up during the sessions for the single “What Difference Does It Make?” in the fall of 1983. Morrissey disappeared from the Manchester studio without explanation, keeping the rest of the group kicking their heels until a phone call five hours later from Travis, informing them that the singer was now sitting in the Rough Trade office in London having walked straight from the studio onto a train. Morrissey wanted to clarify the group’s financial arrangements, believing that he and Marr should earn 10 percent of the group’s earnings, a higher percentage than Rourke and Joyce. Unable to confront the rest of the group directly about it, Morrissey’s way of dealing with it was to go straight to “the boss.” (This uneven division of the Smiths’ royalties would eventually boil over into a 1996 court case, in which the rhythm section denied they had ever formally agreed to this arrangement.)

In the face of such unpredictable behavior, Rough Trade became a kind of surrogate manager to the Smiths, providing them with emotional, logistical and financial support. Travis, for instance, brokered their deal in the U.S. with Sire Records. Publicist Shirley O’Loughlin recalls “spending a whole week trying to figure out this problem of how to get the band from Top Of The Pops to the airport to get a flight to Glasgow in time to play, and I booked this helicopter to land behind the place, got permission from the council in Shepherd’s Bush … and two days before, Morrissey didn’t want to go in a helicopter—I never thought about that.”

Handling the Smiths necessitated a steep learning curve for Rough Trade. The label had initially advanced the group £4,000. Recording The Smiths, which came out in February 1984, had racked up £60,000—a vast sum, especially given that Morrissey and Marr ended up disgruntled about the album’s sound quality. Morrissey was usually disappointed with their chart placings—the highest the Smiths achieved was with “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now,” a number 10 in May 1984—and blamed a sluggish promotional department for failing to produce posters. Meanwhile, Rough Trade’s distribution struggled to fulfill orders of a magnitude it had never experienced before. In March 1984, Rough Trade moved its operations across central London to a warehouse on Collier Street, near King’s Cross. The move coincided with the release of the re-recorded “Hand In Glove” with Morrissey’s heroine Sandie Shaw on vocals—a record that should have gone higher than number 27, but thousands of copies simply became invisible, packed up in cardboard boxes for the move, and were not rediscovered until after the single had peaked.

Rough Trade’s character was shifting in other ways, too. The Fall’s Mark E. Smith took his group off the label, apparently rankled over the favored treatment of a come-lately, younger set of clean-cut Mancunians. His bitterness came out in an end-of-year article published in the NME in December 1983: “A good laugh … was seeing all the serious/literal musicians go ‘Lite’ (in wake of lager and cigarettes) as the scrambling for market position heated up … Competition fierce, and groups as clean and accommodating as never before!”

Was Smith being fair in his assessment of Rough Trade’s new breed as “clean and accommodating”? There was no doubt that Aztec Camera, the Go-Betweens, Prefab Sprout and the Pastels possessed a demonstrably different sound from the first generation of Rough Trade’s post-punk groups. The urgency and abrasiveness of the first wave was gradually giving way to a lighter, janglier tone and a more personal, whimsical romanticism in the lyrics.

Australia’s Go-Betweens, formed around the songwriting partnership of Grant McLennan and Robert Forster, relocated to London in 1981 to try to make a success of their group. They developed a niche of evocative, almost Proustian autobiographical songs. 1983 single “Cattle And Cane” recalled McLennan’s childhood in the Australian countryside, and the Australasian Performing Rights Association later designated it as one of the 10 best Australian songs of all-time. Newcastle-Upon-Tyne’s Prefab Sprout aired its first songwriting efforts on Rough Trade with 1983 single “Lions In My Own Garden: Exit Someone.” Singer Paddy McAloon’s tortuous-yet-witty verse was set to music that verged on saccharine, lite-jazz chord changes, with a sun-drenched pastoral feel. Microdisney, an Irish outfit, specialized in similarly complex, lush song arrangements—by Sean O’Hagan, later of the High Llamas and Stereolab—to complement the vocals of Cathal Coughlan. Glaswegians the Pastels’ “I Wonder Why” echoed the inspired amateurism of the Television Personalities but lacked the self-deprecating humor.

Aztec Camera looked like the second most radio-friendly of all Rough Trade’s new flagship acts—after the Smiths. The band’s trademark jangle and Roddy Frame’s catchy choruses were accompanied by bouncy 12-string strumming on singles “Pillar To Post,” “Oblivious” and “Walk Out To Winter.” Independent music was being recast as songs by and for sensitive, thoughtful, shy, starcrossed boys with a poetic bent. Aztec Camera was signed by Warner Bros. in late 1983, and the reissued version of “Oblivious” saw the group finally make that long-awaited Top Of The Pops appearance on November 17.

Meanwhile, Travis was navigating an increasingly fractious relationship with the Smiths. The group zoomed into the national consciousness through 1984 and 1985, but Morrissey was constantly disappointed with the lack of promotion and any number of nitpicks regarding artwork and posters. (“They released ‘Shakespeare’s Sister’ with a monstrous amount of defeatism,” Morrissey told the NME.) Only too conscious of the fact that they had become a desirable proposition for a larger company, the Smiths were becoming frustrated with their Rough Trade contract, which tied them in for at least another two LPs.

In November 1985, the group assembled at Jacobs Studios in Farnham, Surrey, to kick off the main sessions for The Queen Is Dead. Like Rough Trade, the group was having internal communication issues of its own. Rourke and Joyce were coming to terms with the dawning realization that they were, in effect, being treated as hired hands by Morrissey and Marr. Furthermore, Rourke was fighting a private battle with heroin addiction, and Morrissey had developed a dysfunctional communication style, using intermediaries such as Marr when he wanted to fire a lawyer or give difficult instructions to the other two members.

During their winter residency at Jacobs Studios, the group fielded calls from several interested labels, including EMI, Virgin and WEA. EMI’s offer particularly impressed them, and the general feeling in the Smiths camp was that they would soon be leaving the embrace of Rough Trade. The band was emboldened by “an absolute shark of a lawyer,” as Marr once described him, although the individual has never been named. But Travis fought back. Having caught wind of these backstage negotiations, he slapped an injunction on the group, preventing the release of any new Smiths material on any other label. The wrangling only ceased midway through the following year, when the single “Bigmouth Strikes Again” was released in May 1986 as a preface to the unveiling of The Queen Is Dead in June. The stand-off meant that an unprecedented eight months had elapsed with no new Smiths music since the previous September’s “Ask.”

During this absence, things got out of hand. Marr was stressed out by the recording sessions being constantly interrupted by their lawyer’s visits, phone calls from van companies wanting payment and his delicate position as intermediary between Morrissey, producer Stephen Street and Rourke and Joyce. In January, Marr bungled a 4 a.m. raid on Jacobs Studios to steal the Queen Is Dead master tapes. Rourke was temporarily sacked (in the form of a note attached to his windshield) in an attempt to force him to deal with his heroin problem; a week later, he was arrested in a drug raid, although let off with a suspended sentence and allowed back into the group in April.

The group’s frustration with Rough Trade had turned into profound disillusionment, and one song on The Queen Is Dead made it personal. “Frankly, Mr. Shankly” is a comical music-hall stomp that belies a direct attack on Travis, couched in the form of a resignation speech by a disgruntled clerical worker. “I’d rather be famous/Than righteous or holy any day” was directed at the label’s right-on reputation, while the line “I didn’t realize you wrote such bloody awful poetry” apparently refers to a humorous message Travis had sent Morrissey in the form of a poem. Morrissey didn’t buy this attempt to communicate with him as one creative soul to another, and he used it as one more weapon against the hand that fed him.

“I did feel a certain sense of betrayal,” admits Travis. “I think we learned the lesson that if musicians always think the grass is greener on the other side, they need to go and experience it. ‘Why aren’t we riding around in our own Boeing 747 with our name emblazoned on the side?’ It’s all that kind of mentality. ‘We want to be riding around in limousines, and if we’re so great, why aren’t these things happening?’ That’s a very easy way of displacing underlying problems, by focusing on that kind of rubbish. I think we did a good job with the Smiths, and I don’t have any regrets about that. I wish them nothing but well, but I don’t think they could really say that they underachieved while they were with Rough Trade. In a conventional sense, they did very little, in that they [only] toured America one and a half times. They still sold about half a million copies of every record, which is pretty decent.”

The Smiths were finally severed from their Rough Trade contract in July 1986, even as The Queen Is Dead was basking in critical acclaim and achieving strong sales. After one more album, the Smiths would be free to move from Rough Trade to EMI. The new contract was signed the day before the group flew to the U.S. for a 27-date tour. It was a victory for the Smiths, but a hollow one, because they were to split up before their final Rough Trade LP was even in shops.

The Smiths commenced recording their contract-ending LP as soon as possible, in January 1987. The work at the Wool Hall studio in Bath was conducted in an atmosphere of good humor and even hedonism (during the hours the teetotaling Morrissey wasn’t there, at least). Even so, soon after they wrapped the Strangeways, Here We Come sessions in April, a great deal of bad feelings blew up between Marr and Morrissey. They had appointed yet another new manager, Ken Friedman, who had a divisive effect on the group. Marr, desperate for someone else to shoulder the burden of handling their day-to-day business affairs, was in favor of Friedman, and a familiar pattern of behavior emerged. As Marr got closer to the manager, Morrissey grew to dislike the manager. Marr realized that this situation was never likely to change, and he could see no way out of the predicament.

In May, Marr gathered the group at a fish-and-chips shop in Notting Hill and informed them that he wanted to quit the Smiths. He was persuaded to stay on and record two more tracks for use as the b-sides to “Girlfriend In A Coma,” but the brief taping was dogged by barely concealed hostility between the four members and an almost complete communication breakdown. In a press release sent to the NME in August, Marr officially confirmed the rumors that he had left the Smiths.

Strangeways, Here We Come was released one month later. Instead of ushering in a brave new chapter in the Smiths’ life, it turned out to be the last word. It contained one last kick in the teeth at Travis’ expense: “Paint A Vulgar Picture” co-opted record-company marketing speak and satirized the kind of language that Morrissey must have heard echoing around the meeting table at Rough Trade: “Reissue! Repackage! Repackage!/Re-evaluate the songs/Double pack with a photograph/Extra track and a tacky badge.”