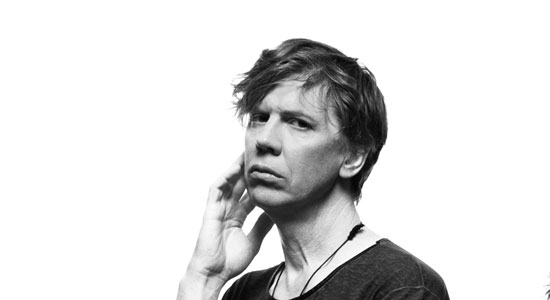

Thurston Moore has been the eternal New Yorker for so long that talking to this citizen of Stoke Newington, England—a pleasant London hamlet where he’s lived since 2013—still feels odd. Maybe it’s also due to his beginnings as a dedicated follower of the late ’70s no wave movement and its reinvigoration via Sonic Youth and the noisiest aspects of Moore’s early solo efforts. Forward motion is his thing. He’s also embraced the language of enlightenment and political rhetoric on his new album, Rock N Roll Consciousness, as well as several purposely non-LP singles. To go with all this, Moore is the subject of a new book, We Sing A New Language: The Oral Discography Of Thurston Moore. —A.D. Amorosi

We spoke when you first moved to England. How does it feel now that you’re firmly ensconced? Got favorite restaurants and haunts?

Totally. London is a massive sprawl of a city. Coming from NYC, London is quite another universe. When I first got here, I heard that London reveals itself very slowly and personally. That’s certainly been the case. I definitely have my favorite bookstore, record store, charity shops. Those are the places I like to go to—I find meditation in secondhand bins. I like that world. The food is also better than when Sonic Youth toured here in the ’80s. England was devoid of a cookbook then.

I lived in Bayswater throughout the entirety of 1982, and all I had was the only 24-hour KFC in Europe. Homey Indian restaurants and tiny fish-and-chip shops were my salvation.

Definitely. That said, I’m still a U.S. citizen. I like that. Being here in London, I am an outsider—an other—while still being welcome in my neighborhood. It’s so entirely provincial with its little villages interconnected, each with their own personality.

So all this love of your new land, but what might you feel going forward with Brexit?

I don’t think it affects me, and far from me commenting on the minutiae of English politics. It was, however, sold to the public with the patina of racism. That’s disturbing, reprehensible and psychically damaging to people in London in particular, because it’s such a progressive bubble. The surprise was that so many left-leaning people here actually entertained Brexit. As always, I am about the further eradication of borders, imposing divisions and being exclusionary. I disregard nationalism of all stripes. I like cultures with their own languages, existing with their own vocabularies and traditions.

Well, you’re not missing much not being in the U.S., if that’s how you feel.

It’s impossible to see what’s going on in the crystal ball because there are so many smoke screens. I’m American. I did not renounce citizenship. Still, it’s hard to watch my country being poisoned by racist, sexist inanity. I have a 23-year-old daughter who lives in the States, and for her to be represented by a president who uses the language of rape culture and the manifestation of hate speech is disturbing.

Speaking of the motherland, old friends such as Richard Hell and Lydia Lunch appear in Nick Soulsby’s We Sing A New Language.

I’m just a cipher in that book. I hardly have any verbiage. The author is cool. Just like his book on Nirvana where he contacted artists around them—headliners when Nirvana was the bottom of the bill, men who made their posters—this ties together the threads of my solo career with arcane label proprietors and such from the time when I was just getting interested in experimental music.

You mentioned your daughter, Coco. Now, it’s not as if you spent a lifetime doing beer, car and lifestyle music. Yet your poetic sensibilities on new songs “Cease Fire” and “Chelsea’s Kiss” have become more pointed and political than in your past.

Any person working in any creative discipline gets changed having children in terms of activism as an artist. I think it’s my age. At near-60, I’m motivated by wanting to be in opposition to an ideology that borders on fascism. To articulate it as a writer means more than just saying it to myself. Now, the whole of my new record stepped away from such direct commentary. I wanted the sound of beauty, something beatific here—but with genuine melancholy, which is always part of the human condition. Yes, there is honor in opposition.

But Consciousness is positivist and aware and un-angry about it.

This just made sense. Yoko Ono once told me something about activism in music. She thinks that you go out and you talk about people with the energy of goodwill in terms of humanitarian concerns and you don’t name the enemy. Once you name the enemy, you become the enemy. I took that to heart. That’s a curious, yet constructive, way of thinking.

You may have worked with another lyricist on some of Consciousness (poet Radieux Radio, a pseudonym for someone Moore is keeping anonymous), but the focus is singular: good energy. Why so?

I had some words, some lyrics unfinished, and as the clock was ticking I turned to Radio. Radio finished many songs I started, which is something that would happen a lot within Sonic Youth, where someone else would pick up what another of us was saying. On this album, we came up with just the right, most sensitive words on feminism, and the energy and power of oracles. And, of course, Mother Earth. Why? Because it was right. There was no thought toward the current political climate, either, as these songs were written and recorded over a year ago, yet they held great portent. Plus, they are beautiful to sing, which is the most important thing.