The making of the Afghan Whigs’ Congregation

By Matt Ryan

There are many remarkable things about Congregation, the Afghan Whigs’ third record, but topping the list is the fact that it ever saw the light of day. The problem, first and foremost, was that the band was particularly adept at breaking up.

“Yeah,” laughs bassist John Curley, “we broke up on a fairly regular basis. I would chalk it up to strong personalities and young guys who hadn’t learned how to communicate very well yet. It’s hard driving around in a van. It didn’t really feel like it at the time, but looking back on it, we really did a lot of miles and a lot of shows. You’re around the same people all the time, and oftentimes scraping together enough money to drive to the next town or share some food at Taco Bell. It’s not an ideal situation. It’s fun and romantic, but it’s stressful, too.”

“We broke up before we even got signed to Sub Pop,” says singer and principal songwriter Greg Dulli. He goes on to explain that the band decided to play two final shows—one in Chicago, one in Minneapolis—the latter at the encouragement of a bartender named Lori Barbero, who is now better known as the drummer in Babes In Toyland. “We ended up having such a good time that we got back together and made Up In It,” says Dulli of the band’s first record for Sub Pop. A subsequent European tour saw the group split again in Amsterdam, each member going his separate way. “We were quite the dramatic, soap opera band,” says Dulli. “We were kind of wild, you know? We liked our poisons.”

In the wake of this latest dissolution, Dulli began writing songs, including “I’m Her Slave” and “Let Me Lie To You,” that he assumed would appear on a solo record. Eventually, he would move from L.A. to Chicago and reestablish phone contact with Curley, which in turn led to Dulli meeting up with the band in Cincinnati to work on some songs. Notably, these early sessions yielded Congregation’s first single and indie-level hit, “Conjure Me.” Unfortunately, the band’s troubles were far from over.

The second roadblock came during the actual recording of Congregation, a time when Sub Pop was circling the drain. “Until Nirvana’s Nevermind came out, actually six months to a year after Nevermind came out, we were not on firm footing financially,” says Sub Pop cofounder Jonathan Poneman. “One of the manifestations of that was inconsistent ability to pay out studio bills. There’s a famous story that Greg can articulate about him getting stranded in Los Angeles because we basically didn’t have money to fund the recording according to the agreement we had come up with.”

“The Congregation album at that time was kind of an expensive record,” says Sub Pop cofounder Bruce Pavitt. “I remember ’91 was a very, very difficult time for the label. We laid off most of our staff. That August, we released Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge by Mudhoney, which wound up selling 100,000 copies, and that really revived the label. And then by Christmastime ’91, we realized that Geffen was going to send us a check for half a million bucks. So, right before Congregation came out, we knew we were back on our feet, but at the time Congregation was being recorded, we were totally broke. It’s a miracle we paid off that recording. I remember Mark Arm from Mudhoney saying, ‘Look, Mudhoney is making all the money for Sub Pop. What you’re doing is subverting those funds and you’re giving it to a band that isn’t even from here.’ He was right—that was exactly what was going on. At the same time, we really had a deep faith in the Whigs to come up with a brilliant record, and they totally delivered.”

Pavitt mentions that the band received a $15,000 advance for Congregation, but Dulli remembers it differently. “We didn’t get an advance; they were paying as we went,” he says. “I was working with this guy who was not really sympathetic to the Sub Pop plight. It was recorded in fits and starts, and I remember being locked out of the studio and I had to call the guy and make threats against his property if he didn’t give me my tapes. That kind of became an agitated situation. Sub Pop went broke. I got stuck down in L.A., and then Nevermind came out. That sort of set me free, in a way. I remember going to Nirvana’s show at the Palace and personally thanking them.”

The studio in question was Buzz’s Kitchen outside of L.A., where overdubbing and mixing occurred following a week or so of recording at Seattle-area studio Bear Creek. By all accounts, the band loved Bear Creek—so much so that they would later record Black Love there in its entirety. Buzz’s Kitchen? Not so much.

“Bear Creek is where it started, and then we moved to some shithole out in Sun Valley,” says Dulli. “It was just bad. My least favorite studio I’ve ever been in. I think the engineer moved us. Kind of sold us a bill of goods. Told us we were going to a studio in L.A., and it was Sun Valley and technically L.A. County, but not exactly Los Angeles. We got kind of swindled there and ended up in a really hot, crowded box in the middle of a not very savory part of town.”

The engineer in question was Ross Ian Stein, recommended to the band by Shawn Smith, a Seattle singer/songwriter who provided backup vocals on Congregation’s “This Is My Confession” and “Dedicate It.”

“I did not get along with Ross Stein,” says Dulli. “He was in my way. I never saw hide nor hair of that guy ever again. I remember it’s the last time I was going to take advice from Shawn Smith.”

“It really ended up being a contentious relationship,” says Poneman. “Because Sub Pop was a fancy name and we were good at corralling headlines at the time, but we were also famously broke, Ross was very concerned about getting paid, which is understandable.”

“I remember the sessions being kind of antagonistic,” says Dulli. “But in a strange way, I think that worked to the songs’ advantage, because it’s a prickly record, you know? I can feel the tension on that record, and it is very real.”

Congregation is indeed a prickly record, but also a huge artistic leap forward for the Afghan Whigs. Most critically, the songs began to reveal the band’s love affair with soul and R&B that would increasingly come to the fore in later records. On this point, it is especially instructive to compare and contrast Congregation with the record that preceded it, 1990’s Up In It.

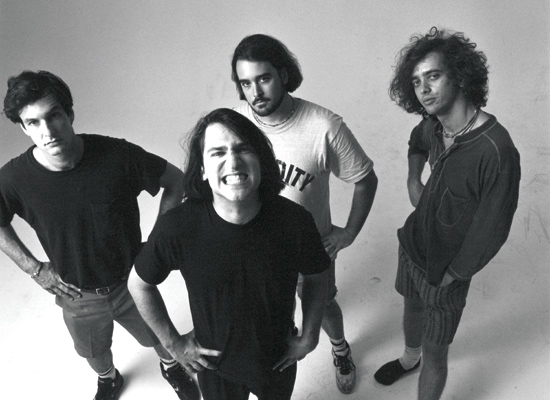

Up In It fit right into the Sub Pop aesthetic at the time. The black-and-white artwork. Charles Peterson band photography. Jack Endino manning the boards. The grungy guitars. If you didn’t know better, you could be forgiven for thinking the band came up in the Seattle scene.

“Up In It had a lot of feedback and screaming,” says Poneman. “People who have followed Greg for the 25 years he’s been making music that you’re now familiar with, the ballads and the more moody, soulful side of what he does, that was all new with Congregation. It was a much more confident record than their preceding ones, but it was also the first record where he was asserting the vision or asserting the kind of musical identity that would become a signature in the works that would follow with the Twilight Singers, Gutter Twins, Whigs, everything he’s been involved with. It can all be traced back to Congregation.”

Dulli speaks fondly of the Up In It sessions with Endino, but for Congregation, he explains that he had very specific ideas about the music, which would involve experimenting outside of the confines of the stereotypical Seattle sound.

“We had spent a year on the road, and prior to the breakup, we had begun playing a lot of the R&B cover songs,” says Dulli. “There was a great deal of texturing happening in the sound before we even got to making the record. It was all stuff that we had liked before, but either hadn’t gotten around to playing or were finally able to play. I think when we started to make the record, the material alone dictated that it was going to have a different sound.”

“What also made Congregation so great is the band had been doing a lot of touring,” says Poneman. “Greg had gotten a lot of confidence. The band as a whole. I mean, John Curley’s contributions cannot be understated; neither can (guitarist) Rick McCollum’s. Steve Earle was a great drummer. That’s germane to this conversation, because it wasn’t just the maturation of Greg’s vision. While that was obviously key, he being the principal songwriter and singer, the band as a whole, their sonic palette had expanded considerably. Their confidence had expanded considerably.”

“At the time Congregation rolled around, I think everyone was feeling a little more confident as musicians, as songwriters, as a band,” says Curley. “I think that comes across in the difference between Up In It and Congregation. I also think we got more comfortable in the studio. We did more guitar overdubs and tried to take advantage of what the studio had to offer and being less constrained by thinking we had to do it exactly the way we played it live. And I think also because we had written some of that stuff separately, by making demos, it sort of started out that way.”

While the Afghan Whigs were maturing as musicians, Dulli was also coming into his own as a lyricist. With Congregation, his words would garner both critical praise and controversy, as he explored relationships and sexual politics through a decidedly dark lens. This is revealed most vividly on “This Is My Confession,” where he acknowledges to a lover that “you were only meat to me,” and on “Conjure Me,” where he warns that “I’m gonna turn on you, before you turn on me.” Equally dark, “I’m Her Slave” shifts the power dynamics, with Dulli playing the submissive (“I don’t need no chains, I’ll behave”) to his neighbor’s wife. How much of this is truly reflective of Dulli’s life versus just him inhabiting a character?

“I wish I could remember,” says Dulli. “It’s half my life ago. I don’t know where I end and the character begins and vice versa. I’m trying to think how old I am there. Early 20s. You’re figuring out who you are. You can say things in songs that you can’t say to someone’s face. It’s like the difference between writing a letter and making a phone call. A phone call, you can get really emotional, you can get interrupted. Writing a song is like writing a letter. You have time to sit with it. The other person can’t interrupt you while you’re making your point. I’m guessing it’s probably a hand in hand of my actual feelings and inhabiting a character. I’ve often said that no one person’s life is so interesting that they could write a whole album about it.”

“Greg Dulli is a great singer and a great tunesmith, but his greatest gift, in my opinion, is as a lyricist,” says Poneman. “Imbuing those lyrics with real emotion. I so loved a lot of what he sang about and wrote about on Up In It, so I was very psyched to hear Congregation. I think it’s kind of simplistic to refer to it as being misanthropic explorations, but he did explore a lot of darker behaviors. He uncovered them in little bits on Up In It, but it became more full blossom on Congregation.”

Despite Dulli’s emerging gifts as a wordsmith, the band did make a seemingly baffling decision to include on Congregation a cover song from Jesus Christ Superstar, “The Temple.”

“Jesus Christ Superstar is a record that John and Rick and I had in common from our childhoods, and it was one of the first things we bonded over,” says Dulli. “I really loved Ian Gillan as the Jesus voice and really loved the songs. We would play several of those songs in early shows. Still to this day, we’ll occasionally play ‘Heaven On Their Minds.’ We had played ‘The Temple.’ We had played ‘Gethsemane.’ I had mashed in ‘I Don’t Know How To Love Him’ into songs early on, so just kind of a record that I absolutely adored and had memorized.”

Cover songs aside, another area in which Congregation was both a great leap forward and a noticeable break from the Sub Pop aesthetic was in its striking cover art. In sharp contrast to the label’s penchant for black, white and grays, the cover photography was rendered in vivid color, with no text. On a bright red blanket sits a nude African-American woman cradling a white infant, a not-to-subtle acknowledgement of the band’s love for, and debt to, African-American music.

“The cover art of Congregation is very powerful,” says Pavitt. “I do remember when Greg came in with that image. It’s very appropriate to what they were trying to do with their nod to, a lot of respect for, black musical culture. I remember being very impressed and blown away by not only the photo, but the fact that they were doing a cover with just no text, which underscored the power of the photo.”

“Congregation was going to be a real assertion of the band’s identity over them being, you know, grunge also-rans,” says Poneman. “This was going to be the full-color lusciousness of the cover of Congregation as juxtaposed against the gray, black and white cover of Up In It. That to me suggested a deepening of sonic hues, as well as the visual aesthetic that the band would put forward.”

Dulli puts it more succinctly: “I think some bands in Seattle had taken issue with our declaration of love of soul music. I think we were goofing on some people’s opinions of us and decided to take it to a visual extreme.”

“Seattle was very insular, and Sub Pop by extension,” says Poneman of any tensions between the Afghan Whigs and the Seattle scene. “A lot of the musicians hung out together. If there were strangers, there was probably a little bit more skepticism. The Whigs were not a known entity when they first came onto the label. By the time Congregation was being created, they had proven themselves over and over again as a live band, and they had drawn and built a real fan base.”

With the recordings completed and final artwork in place, after more than a year of excruciating labor pains, Congregation was finally ready to be delivered. Of course, the Afghan Whigs, as we’ve seen, aren’t predisposed to do things the easy way. How else to explain adding a track so late in the process, it didn’t even make it onto the album sleeve. It turned out this hidden track, ‘Miles Iz Ded,’ would become a fan favorite. The song starts with a martial drum beat and a churning guitar, while Dulli, in his best lascivious croon, sings, “What if I stepped it off?/Walked outside your trance/Crawled inside your mind/And got my hands into your pants/Wouldn’t that beat all?/Wouldn’t that be great?” The band then launches into the kind of chorus that makes audiences go apeshit, all explosive guitars and Dulli’s howls of “Don’t forget the alcohol!”

Dulli provides us with the song’s origin story. “I was living in California and was on my way to work at Rhino on Westwood,” he says. “Miles Davis had passed away and someone had spray-painted ‘Miles Iz Ded’ on a building. Later that day or the next day, I was on my way to a friend’s house, Dave Katznelson, who worked at Warner Bros. at the time. I was hanging up the phone and on the way to his house party, and he said, ‘Don’t forget the alcohol.’ And that was the last thing I heard before I hung up. As I was driving over, I just kept repeating, ‘Don’t forget the alcohol,’ in my mind. I had already begun working on a song that has those chords, and he essentially gave me the chorus to that song.”

So, did he bring the alcohol? “I did,” says Dulli. “I’m pretty sure I stopped at Liquor Locker on Sunset near Chateau Marmont.”

With Congregation finally released to the world, the Whigs embarked upon the longest tour of their career, some 200-plus shows, and later would go on to more breakups and reunions. Along the way, they recorded another classic, Gentlemen, and in their most recent incarnation (without McCollum and Earle), 2014’s Do To The Beast, which also sees the band returning to Sub Pop after a stint in the majors.

For his part, despite all the travails, Dulli looks back upon the Congregation era with affection. “I learned a lot about the world, because I went around it several times,” he says. “It put rock ‘n’ roll as deep into my blood as it had ever been before. When you get to play every night, that part of it was a dream come true for me. I felt invincible. I actually have fond memories of it. Even the shitty times were fun. It was, at the time, the culmination of all I ever wanted to do when I was a kid. To play in a rock ‘n’ roll band and travel the world. I was very, very grateful for it.”