At this point, I believe I qualify for dual citizenship as an honorary Norwegian. No, I haven’t spent the last 20 years living in Oslo or working at the Edvard Munch Museum. I don’t speak Norwegian. I can’t even play “Norwegian Wood” properly on my acoustic guitar.

What I have done is read the first five volumes of My Struggle, the six-volume monstrosity—part novel, part memoir—by Karl Ove Knausgaard. The sixth volume hasn’t yet been published in English, so I’m as caught up as I can be without learning Norwegian.

There’s been a lot of hype about Knausgaard’s magnum opus. The Guardian has called it “perhaps the most significant literary enterprise of our time.” More than a half-million books have been sold in Norway, a country with a population of about 5.2 million human beings. An American author would have to sell more than 30 million copies to have that kind of market penetration.

But there are other things. Knausgaard has been criticized for writing so openly and honestly about his life, which by necessity means writing just as openly about other people. He names names and reveals family secrets that are bound to be painful for other members of his family and inner circle.

And then there’s the title: “My struggle” in Norwegian is “min kamp.” In German, of course, that translates to “mein kampf,” which causes shudders because it was the title of Adolf Hitler’s autobiography and manifesto.

That’s not an accident. The sixth and final volume of Knausgaard’s work reportedly includes a several-hundred-page discussion of Hitler’s book and its relevance. While I can’t say I’m looking forward to reading that, I also think it’s fascinating to ponder how Knausgaard handles the subject.

In a way, the use of “mein kampf/min kamp/my struggle” is the kind of provocation that was pretty common during the punk era. Early English punks sometimes used swastikas to shock and offend people—remember, they were trying to disturb their parents, a generation that grew up amid World War II bomb sites. To an English punk in the 1970s, Nazi imagery was akin to an American band calling itself the Dead Kennedys—meant more to shock than to signify any particular ideology.

(To clarify: There certainly are neo-Nazi punks, as well, but a lot of that imagery was not being used because of ideology. The Ramones’ “Blitzkrieg Bop” and Elvis Costello’s “Two Little Hitlers”—or the reference to the “final solution” in “Chemistry Class”—don’t signify some kind of serious fascist beliefs. At least, I hope not.)

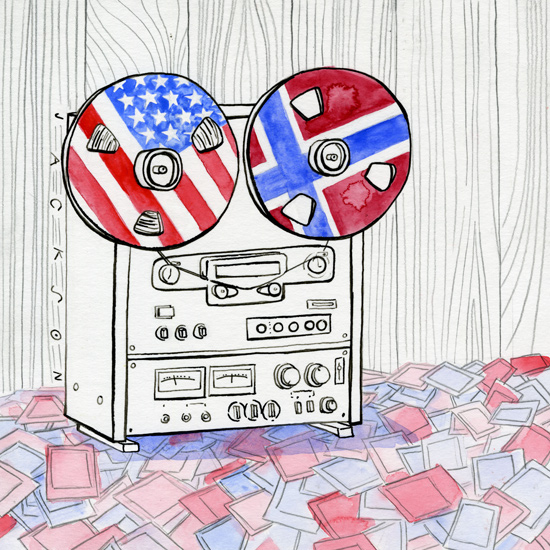

Punk rock is an apt comparison because of another key element in Knausgaard’s books. Music plays a large and recurring role in the story of Knausgaard’s life. For me, an American of a similar age, Knausgaard’s fascination with music provides familiar landmarks. I know where I was in my life when Echo & The Bunnymen were on the stereo. And there’s a connection when Knausgaard refers to less-hyped bands, such as the Waterboys or Prefab Sprout.

But here’s the main thing. It isn’t so much particular bands that make this reader feel a connection to that particular writer. It’s Knausgaard’s perception of the world with music as an important element. He bonds with fellow students over the love of a particular band, and he feels alienated from people with dramatically different taste in music. When he meets a stranger in a new town who likes heavy metal or mainstream radio fodder, he knows that person won’t likely become a friend.

At one point, Knausgaard makes extra money by selling used CDs outside of a shop. At another, he plays in a series of bands, usually with his older brother Yngve. Karl Ove writes lyrics that his guitarist/brother puts to music. Playing live, Karl Ove is the drummer.

That, too, is universal, the compulsion to take up an instrument and reproduce some of the music that you love (and impress the opposite sex, but that’s another chapter). It’s the same compulsion that drove many of the bands on the CDs that Knausgaard buys and sells. The really great thing here is the way that compulsion, that need for self-expression, leads a group of young English or Americans to create songs that wind up on a mixtape made by a lovestruck Norwegian kid who they’ll never know exists.

Well, except that we now know that Karl Ove Knausgaard exists. We know that he wrote record reviews for a while, that he lost his virginity in a tent at an outdoor music festival, and that he somehow wound up in Björk’s house, drunk, during a trip to Iceland.

Look, you read five or six books by anyone and you’re going to start feeling like you know them. When the books are as personal and revealing as My Struggle, then you’re bound to feel that much more connected to the writer. It’s inevitable.

The importance and prevalence of music in Knausgaard’s life definitely increased the level of intimacy for this reader, or for anyone who has gotten through difficult times by cranking up the stereo, or has found kindred spirits through a shared love of some obscure band.

There has to be something universal in a book (or books) like this if millions of people are going to connect with it. That’s obvious. But sometimes it’s not the universal but the very specific that hits hardest. And there’s nothing more specific than the music that was playing during key moments of a life. For me, the music is the bridge that connects my American sensibility to Knausgaard’s Norwegian one. We lived in thoroughly different parts of the world, but we had similarly human experiences accompanied by a very similar soundtrack.

Music made my own struggle feel like My Struggle. Plus it probably saved me a trip to Norway. Walking around Bergen isn’t going to make me feel any more connected to that time and place than listening to some Bunnymen.

—Phil Sheridan