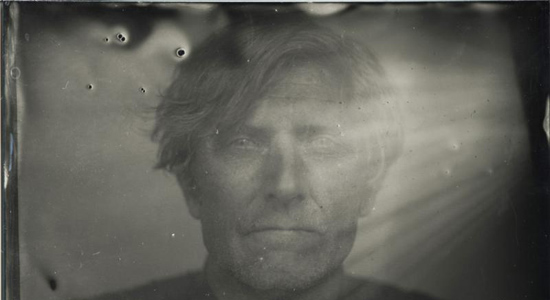

Eclectic fearlessness ignites country journeyman Stone Jack Jones’ triumphant return

By the time he reached 55, Stone Jack Jones had spent a lifetime as a carnie, ballet dancer, lute player and hundreds of other things, trying his luck from Buffalo Creek to Charleston to Boston to New York to Fort Worth to Atlanta to Nashville. Mostly, he made music—even if it was just playing on the street or at a nearly empty open mic. Then in 2003, he met Roger Moutenot, who’d engineered albums for They Might Be Giants, Yo La Tengo and John Zorn. And all of a sudden, something happened.

“Our wives knew each other, and Roger needed a temporary place to mix,” Jones says from his Nashville home. “I had a studio—it didn’t have any recording equipment, but I call it a studio, and we agreed to share the space. That first night, he walked in while I was playing, and just stood there. He goes, ‘I thought you played country music.’ And I said, ‘Well, I thought I did, too.’ And he goes, ‘I don’t think that’s country. Let’s try recording it.’”

So they did. The song was “Johnny Boy,” about a guy looking for a fix, with lines like “I was simply dreaming I was dreaming in a dream.” It started with Jones singing and strumming acoustic guitar, but by the time they were finished, there were thick, dark layers of guitar noise on top of a fuzzed-out organ, wobbling bass, echoing drums, disembodied voices and a high hat that sounded like an alarm clock in the middle of a hangover. Like “Venus In Furs,” if Lou Reed had grown up in a holler. Or “Suzanne,” if Leonard Cohen’s father had been a coal miner instead of a clothing salesman.

“It felt very natural,” says Jones, whose third album, Ancestor (Western Vinyl), keeps working that same vein. “Roger started recording me as though we were live. He has an incredible amount of energy, so if he had a free night, we’d work from nine ’til three in the morning, usually one song a night. It was very spontaneous—more like playing than recording. I felt comfortable working with Roger, and when I heard a song coming out of the speakers, it wasn’t embarrassing. It didn’t sound like a second-rate country singer; it sounded special.”

His first two albums, Narcotic Lollipop and Bluefolk, were pretty damn special, but hardly anybody heard either one. With Ancestor and his upcoming 66th birthday, Jones is hoping that’s about to change. It’s certainly the best of the three, with a deeper sense of home and a sweeter, simpler sadness in the songwriting. On “Joy,” he’s dreaming about the afterlife; on “Jackson,” he’s remembering a better time; on “Black Coal,” he’s thinking about his father, a fourth-generation coal miner who passed away three years ago.

“It was an actually an old song I found myself singing around the house after he died,” says Jones. “It just came back to me and took me over, just out of respect. That was in 2010, when I started on this. Every record has to start from something, and this one started with a string band, just thinking about vibrating strings and the stories they tell. I went in with the bare bones, let myself feel that Appalachian string band, and have it grow from there.”

With Jones multi-tracking on acoustic and electric guitars, banjo, Fender bass, Dobro, harmonica, Hammond organ, Wurlitzer, piano and tambourine, Ancestor doesn’t sound like his father’s folk music. (Or his father’s marching band.) On top of that, there’s e-bow, organ, vibraphone, glockenspiel and high-strung guitar by Lambchop’s Ryan Norris; Casio, Moog, Roland and toy piano by Moutenot; drums processed through a telephone mic; cocktail-party sounds from Nashville and Berlin; and “little blips of weirdness” by Ben Smythe. Pile them all together, slow the tempo down to an opiate nod, and you get a roomful of ambient noise surrounding what Jones calls “a simple, confessional song, humbly presented.”

“The songs aren’t very different from the ones I wrote 30 or 40 years ago,” he says. “The clothing on it—the way it’s dressed sonically—has changed. But underneath, the structure of the songs and the attitude in the songs goes back to very simple country songs, or bluegrass, or old-timey—that ethnic stuff I grew up around. That’s where I started, and I think I’m still there.”

—Kenny Berkowitz