Mike Scott is pop’s only literate lyricist who would dare take on the stately iconography of William Butler Yeats. Forget about the living proof provided by his band the Waterboys as they tackle the Irishman’s prickly poems through a series of 14 daringly diverse arrangements on the new An Appointment With Mr. Yeats (Proper American). You’d know that if you’ve listened to Scott’s richly robust catalog of Waterboys albums made since 1983, or even read his recently released book, Adventures Of A Waterboy. Though imbued with an intellectual curiosity beyond that of the most wizened scholar, Scott has long found himself inspired by Yeats’ vivid world-weary lyrical textures and smartly grammatical manner. On the other hand, he’s a big Twitter fan. Go figure. Scott will also be guest editing magnetmagazine.com all week. Read our new Q&A with him.

Mike Scott is pop’s only literate lyricist who would dare take on the stately iconography of William Butler Yeats. Forget about the living proof provided by his band the Waterboys as they tackle the Irishman’s prickly poems through a series of 14 daringly diverse arrangements on the new An Appointment With Mr. Yeats (Proper American). You’d know that if you’ve listened to Scott’s richly robust catalog of Waterboys albums made since 1983, or even read his recently released book, Adventures Of A Waterboy. Though imbued with an intellectual curiosity beyond that of the most wizened scholar, Scott has long found himself inspired by Yeats’ vivid world-weary lyrical textures and smartly grammatical manner. On the other hand, he’s a big Twitter fan. Go figure. Scott will also be guest editing magnetmagazine.com all week. Read our new Q&A with him.

In 2012, my first book was published, a memoir titled Adventures Of A Waterboy. It’s a memoir about my life in music, from when I first realised I had music in my head as a skoolboy, through my teenage bands, the Waterboys, the years I lived in Ireland, New York and other places, all the way up to 2000. But no further. The recent past is too recent to write about. It hasn’t untangled itself yet.

The following extract is set in 1985, during a short lay-off in London between Waterboys tours.

I checked into a hotel and got a call from an American lady I knew called Rovena Cardiel, a tenacious and pretty hustler who ran the local office of Geffen Records. She was buddies with Bob Dylan’s girlfriend and rang to tell me Bob was in town and that having heard and liked my song “The Whole Of The Moon,” he was inviting me to come and join in a recording session. I asked Rovena if I could bring my Waterboys colleagues Steve Wickham and Anto Thistlethwaite. She checked this out and the answer came back: yes. So on a bleak November afternoon as the wind raced through the streets like a league of phantoms, the three of us jumped in a black cab with our instruments and headed up to north London.

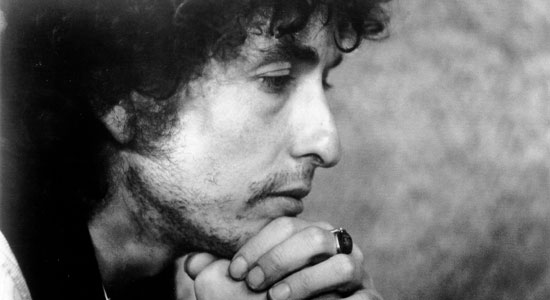

The studio was a converted church in Crouch End. We buzzed the doorbell and climbed a flight of stairs, emerging into what was once the vaulted nave of the church, now the studio’s live room. At the far end was a row of soundproofing screens and sticking up above one of them was a tousled head of curly hair. Yup, it was Bob. We walked round the screens into an enclosure filled with enough instruments for a large band, and in the middle Bob was sitting on his own. His face, so familiar from film and photograph, looked more Eastern in real life, as if he were an inscrutable Chinaman or a Zen Master. He was dressed in jeans and red shirt with a blue scarf, and having shaken our hands—he seemed genuinely pleased to see us—he reverted to his afternoon’s pursuit: playing ceaseless lead guitar, coaxing bluesy sounds from a Fender Stratocaster.

The rest of the band came out of a nearby control room and introduced themselves. The only ones I recognised were Clem Burke, the drummer from Blondie, and Dave Stewart of the Eurythmics, a gangly, nervous chap who functioned as ringmaster, cajoling everyone along and suggesting each next musical activity. We found spaces to sit and joined in on what turned out to be a slow, sexy instrumental. To our disappointment Bob didn’t sing, just kept playing that burbling non-stop guitar, even in the breaks between takes.

In one such break Bob had a short word with each of us. He’d met Steve when his old band In Tua Nua had played support to him in Ireland a year earlier and so he genially, if tactlessly, asked Steve: “How’s your band doing?” For me, he had some kind things to say about “The Whole Of The Moon,” and there was an encouraging word for Anto, too.

When we were all in the control room listening to the instrumental we’d recorded (except Bob, still in the studio playing burbling lead guitar), Dave Stewart asked me if I had any tunes we could do. I scratched my head and went out to the piano. Bob stopped playing and came over. Several tunes came into my mind, but I had them all earmarked for new Waterboys songs and I wasn’t giving them away, Dylan or no Dylan. Then I remembered one that didn’t figure in my plans, a kind of reggae-meets-jazz number called “Say You Will.” Of all the songs I ever wrote it was not the most auspicious one to play as a demo for Bob Dylan. I sang a verse or two, the band joined in and Dylan played yet more burbling lead guitar. When the song finished he walked over to me, put a gentle hand on my shoulder and and said in a kindly tone, “You can keep that one.”