Each week, we take a look at some obscure or overlooked entries in the catalogs of music’s big names. MAGNET’s Bryan Bierman focuses on an album that, for whatever reason, slipped through the cracks in favor of its more popular siblings. Whether it’s new to you or just needs a revisit, we’ll highlight the Hidden Gems that reveal the bigger picture of our favorite artists.

Before they were taking flight onboard the Mothership, Parliament began its trip in a New Jersey barbershop. In the mid-’50s, George Clinton was a hair stylist at Newark’s Uptown Tonsorial Parlor. Located in a predominantly black neighborhood, the shop was the hangout for the young and old. The North Carolina-bred Clinton became well-known for his hair-styling abilities (no surprise there), but also for his musical talents. Along with a few friends and co-workers, Clinton would regularly belt out doo-wop tunes for the delight of the costumers. At first, it was just a fun hobby, but the boys soon found themselves harmonizing in the back room, long after the shop had closed. Clinton soon left the Uptown to start work at Silk Palace, another barbershop in the nearby town of Plainfield, where he recruited a few local singers for his burgeoning group. It was here where the boys focused their musical ambition, and taking the name of their favorite brand of cigarettes, the Parliaments were born.

Beginning in ’58, the group recorded a few singles under various record labels but all struggled to find success. 1965’s “Heart Trouble” single for Golden World Records met the same fate, though it was the first to feature the Parliaments’ classic lineup of Clinton, Grady Thomas, Ray Davis, Calvin Simon and Fuzzy Haskins; this formation would remain for years to come. After producing a bunch of local groups for different labels including Revilot Records, with whom the Parliaments were soon signed, Clinton got a job as a songwriter/producer for Jobete Music, the publishing company of Motown Records. On his weekends off from the barbershop, which he now owned, he would make the trek from Jersey to Detroit to produce recording sessions. On one such trip in ’67, Clinton recorded a song he had co-written, “(I Wanna) Testify,” though as the rest of The Parliaments were unable to attend, the track was filled out by various session musicians and vocal group the Andantes. Released as the Parliaments for Revilot that summer, “(I Wanna) Testify” became the group’s first hit song.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YAR6BBQO8-k

Reaching as high as number three on the Billboard R&B chart, the song was the group’s ticket to freedom. All the members quit their jobs, including Clinton, who soon sold the Silk Palace. Though they were without a backing band, save for guitarist Billy Nelson, the Parliaments threw one together and went out touring the country. Over the next few months, various members would come and go, including drummer Tiki Fulwood, who would remain for a few years. Soon, Nelson switched to bass, replaced with his childhood friend (and future guitar god) Eddie Hazel. The Parliaments now had a steady, and fantastic, musical backbone.

This is where the story gets confusing. After recording six singles for Revilot Records, Clinton and the label had a disagreement over money, and even though the Parliaments were still under contract, the band refused to record for them. Around this time, Revilot filed for bankruptcy, presenting the group with a whole bunch of legal problems. Since the band could not bill itself as the Parliaments, Clinton and Co. decided to name the group’s backing band Funkadelic, which they would then sign to another record label, even though the music would still feature the same five singers. A holding company, dubbed Parliafunkadelicment Thang Inc., was formed, and split among the original members.

It was now 1968, and to quote Principal Seymour Skinner, “The times they are a-becoming quite different.” The culture was changing and the drug era was in full-swing, making the soul and doo-wop of the Parliaments seem old-fashioned. As Clinton explained, “We couldn’t keep our ties alike. Couldn’t keep the suits clean. Hair was always undone. You realize the reality of that was really silly, especially when the hippies had just hit the scene and it was hip to be—you know, funky looking.” The group, now based in Detroit, started experimenting heavily with LSD, among other drugs. And if that wasn’t enough mind-fuckery, they were regularly sharing bills with The Stooges and MC5.

Over the next few years, Clinton and Funkadelic would transform into one of the most innovative, electrifying and downright monstrous bands to ever roam the Earth. With the addition of rhythm guitarist Tawl Ross and keyboardist Bernie Worrell, the band signed to the newly formed Westbound Records in 1970, releasing two albums that year. On these records, they combined the black-pride funk of James Brown, the feedback filled jams of Hendrix and the free-jazz intensity of Sun Ra.

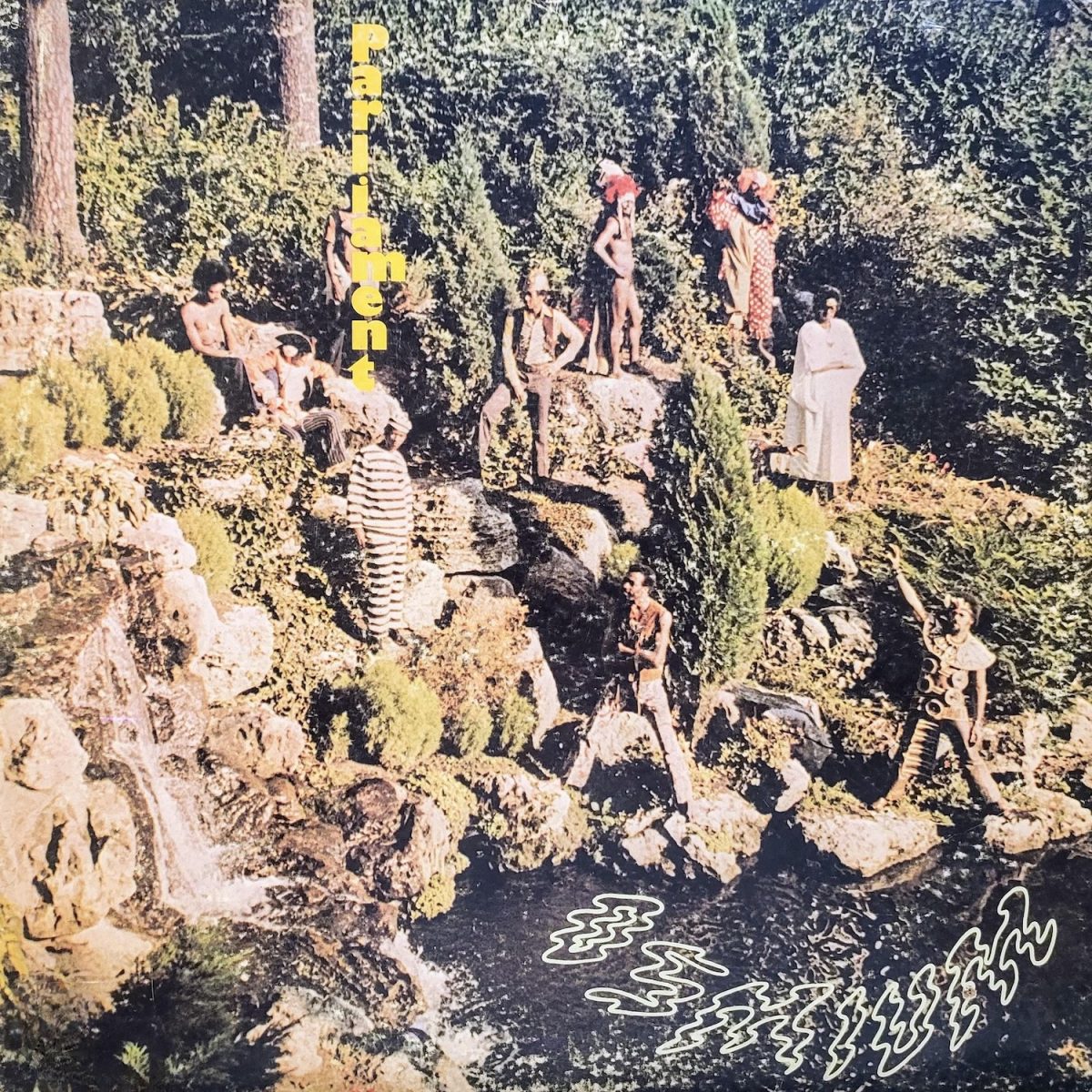

But what became of the Parliaments? In late 1970, the group won back the rights to use the name, but ready for a change, they dropped the “s” to become Parliament. Because of the group’s clever business tactics, Funkadelic had a record deal, but Parliament was a free agent. Producer Jeffrey Bowen, an old friend/co-worker of Clinton’s from his Motown days, soon got in contact, persuading the band to join the Invictus Records, created by Holland/Dozier/Holland, the team that wrote and produced 25 number-one hits for Motown. After signing, the group became friendly with English folk singer (and Jeff Bowen’s wife) Ruth Copeland. She began to collaborate with the group and decided to produce the band’s next album, with the help of her husband.

Osmium presents a different side of Parliament, with a sound unique to any of the P-Funk discography. Here, they tone down Hazel’s giant acid-drenched riffs with Funkadelic (at least somewhat), playing up the vocal stylings of the five singers, by blending in more of a gospel-influenced sound. Among the numerous spiritual themed tracks, “Livin’ The Life” features lyrics that could have come from a church hymn, but the song keeps up a tight groove for Hazel’s guitar solos. Clinton’s North Carolina upbringing mostly likely inspired a few of the band’s lesser-known, but still essential, tracks. “Moonshine Heather” tells the tale of a war widow who is forced to sell moonshine to make ends meet for her 14 children. Why it isn’t more widely considered one of the band’s best moments is beyond me. There’s probably no better way to describe the track’s inherent coolness than this: If a ’71 Oldsmobile 98 could pick a theme song, it would probably be this.

Keeping with the car theme, “My Automobile” begins with a peculiar audio documentary in which the band actually writes the song before our very ears. Clinton shows the group his lyrics, which detail his younger self’s attempts to get lucky in his car, and with the help of Worrell’s quick improvisation skills, the group begins harmonizing like they did back in their barbershop days. The second part of the song is the actual tune, featuring a self-described “hillbilly sound” reminiscent of the Southern rock of the time, which, of course, they put their own funky spin on.

These same recording sessions also spawned Copeland’s debut album, Self Portrait, with featured Parliament as her backing band. Her influence on Osmium can’t be understated, as she penned two tracks on the album, including one of the most gorgeous moments of the band’s career, “The Silent Boatman.” An ode to Charon, the mythical ferryman of death, Copeland’s English folk blends acoustic guitars, harp and even bagpipes with the heavenly vocals of Simon and the rest of the gang.

Although reviews were positive (Billboard said it was “something different and that’s a good sign”), sales of the album and its singles were underwhelming. Some of the band would stay with Copeland to record her follow-up, and the rest went on to a very different sound with the next Funkadelic album, magnum opus Maggot Brain. A few Osmium tracks and outtakes—including “Loose Booty” and “Red Hot Mama”—would later be re-recorded with Funkadelic. (Interested parties should track down the First Thangs CD, which features all of Osmium along with a few related outtakes and b-sides.)

The Parliament name would take a break after the album’s release but would be revived a few years later for Up For The Down Stroke, leading the band to bigger success and much funkier pastures.