Kristian Hoffman and Lance Loud met in high school back in the early ’70s in Santa Barbara, Calif. After starring in PBS cinéma-vérité documentary An American Family, they formed the Mumps, moved to New York and shared Max’s and CBGB stages with all the legends of the punk/new-wave explosion of 1976: Television, the Ramones, Talking Heads and Blondie. Hoffman and Loud also had front-row seats for the Mercer Arts Center incubation of the New York Dolls, before that. In our book, that grants you unlimited license to open the floodgates. Fop (Kayo), Hoffman’s latest solo album, is an ornate masterpiece of baroque pop, well worth your attention. Hoffman will be guest editing magnetmagazine.com all week. Read our new Q&A with him.

Kristian Hoffman and Lance Loud met in high school back in the early ’70s in Santa Barbara, Calif. After starring in PBS cinéma-vérité documentary An American Family, they formed the Mumps, moved to New York and shared Max’s and CBGB stages with all the legends of the punk/new-wave explosion of 1976: Television, the Ramones, Talking Heads and Blondie. Hoffman and Loud also had front-row seats for the Mercer Arts Center incubation of the New York Dolls, before that. In our book, that grants you unlimited license to open the floodgates. Fop (Kayo), Hoffman’s latest solo album, is an ornate masterpiece of baroque pop, well worth your attention. Hoffman will be guest editing magnetmagazine.com all week. Read our new Q&A with him.

Hoffman: I am so thrilled with all the uprising all around the world, from Wisconsin to Bahrain! I know when the dust settles, the outcome is likely to be a little more complex and problematic than, say, the rather naive and slightly Wiccan 1970 burning of the bank in Isla Vista that Lance Loud and I witnessed while crouching in a telephone booth to avoid the tear gas, laughing maniacally and wondering if “now” were a good time to shoplift some more British import versions of favorite Small Faces 45s and mono Beatles LPs from the student record shop.

Hoffman: I am so thrilled with all the uprising all around the world, from Wisconsin to Bahrain! I know when the dust settles, the outcome is likely to be a little more complex and problematic than, say, the rather naive and slightly Wiccan 1970 burning of the bank in Isla Vista that Lance Loud and I witnessed while crouching in a telephone booth to avoid the tear gas, laughing maniacally and wondering if “now” were a good time to shoplift some more British import versions of favorite Small Faces 45s and mono Beatles LPs from the student record shop.

Since the uprising in Libya resulted in actual strafe-drone-tomahawk “intervention” (i.e., outright war!), striking a nonchalant pose about the actual loss of human life may be somewhat untoward. But I still have to say that the supposed “people” (for argument’s sake, let’s not include the corporate construct know as the “Tea Party” in this alumni) grabbing the reins and effecting positive change through sheer force of will and resistance is a magical thing. I surely wish the best for the people of Libya and all the revolutionaries of the Middle East uprising, though I obviously can’t pretend to understand all of the minutiae of their current conflict.

But in an odd way, being informed is beside the point in this article. I just want to celebrate the spirit of uprising everywhere, through the ages! Having been borne of a professional peace activist, where other children might have been dropped off at the spanking new San Roque outdoor mall (“Meet me at the Robinson’s entrance in 45 minutes”), much of my childhood was spent in long stints at sparsely attended candlelight peace vigils outside the Santa Barbara Art Museum, barking tone-deaf de rigeur rounds of “We Shall Overcome” in the family station wagon on our way back to the positively Disney-esque luxury of our house in Montecito. It was called “Rich Person Land.”

My mother was a passionate advocate for everything liberal and fine from our rather embarrassingly lavish dwelling, and all her seven kids were shepherded through arts and music, whatever new fad of self-examination was being touted on the cover of Psychology Today and the spiritual disciplines of the warm SB Quaker community, which we found impossibly boring and only absorbed through reluctant osmosis. And, in our pastoral bubble of financial security, the things we were protesting seemed as dreamlike as Narnia or the Beatles.

But something must have stuck, because now we all resolutely try to out-radical each other, and revolution around the world is not only inspiring, but also oddly nostalgic, bringing back early memories of Joan Baez, Josh White, Pete Seeger and the Weavers being played endlessly on the living room hi-fi (albeit while my dad was in his office with the headphones on, listening to the startlingly hip The 10th Victim and Juliet Of The Spirits soundtracks—stuff I would only discover later because we weren’t allowed to touch his records or his high-end stereo).

So I’ve always had a soft spot for a protest song, no matter what form it took, even though I’m painfully aware of how many times they can slip into insufferable self-righteousness, interminable maladroit verbal self-indulgence and, more often than not, a compositional ability somewhat less sophisticated than “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star.” Take the dreaded “We Shall Overcome.” Please!

Sure, we felt the call of Dylan’s great, iconic catalog of political anthems, in his own voice and in the interpretations by the Byrds and countless others. Sure “Waist Deep In The Big Muddy” is inspiring, and even then we chilled to the counterintuitive chorus of “They Will Know We Are Christians By Our Love.” My mother even bought us our copy of Janis Ian’s first album, with the classic “Society’s Child” on it. That whole album to me is a kind of quasi-psychedelic Sgt Pepper of youthful tart-tongued protest, with these fab lyrics in “Younger Generation Blues”: “Then up stepped three more governmental nuts/Who’d been laying in the gutter, disguised as cigarette butts.” Janis Ian and Donovan helped escort me into a world where I saw that a song didn’t have to be painfully prosaic to be an anthem of resistance; it could be psych-tinged and melodic and as full of surprises as any raga from Revolver.

And the Fugs’ resolutely iconoclastic take on the convention of “protest” was revelatory: Sure, “Kill For Peace” was enjoyable but transparently sub-pre SNL, Harvard Lampoon collegiate comic posturing. But their flatbed truck demonstration during which they cried “Out, demons, out!” in the face of heavily armed National Guard three rows deep outside the Pentagon, whose building the Fugs insitsted they were going to “exorcise and levitate,” claimed a fantastical and ruefully hilarious Dadais-art-as-revolution purview years before the dry academic tropes of “conceptual art” stultified real artistic adventurism into entropy. But the Fugs’ real “protest” accomplishment was “The War Song,” so naked and raw and made all the more penetrating by the seemingly emotionally disinvested, clinically described stylings of an atonal Mothers Of Invention prog/jazz that it is almost as unlistenable as war is unthinkable: “Strafe them creeps in the rice paddy, daddy/Burn, mother, burn/The puke hangs out of the nose/Shattered ganglia twitch out of the dead man’s spine/Mouth choked off with with worms/Slobber and foam/The earth dreams blood/War war war/The meat goes to war/The vultures drool on the skirt/Hissing drops of blood burn inside the smashed babe’s face/Napalm rotisserie cooks the world a meal.”

In any case, the various mid-’60s permutations of the once well-intentioned but musically lumpen hokum known as “protest” rendered it suddenly a vehicle of radical transport toward epiphanies of engaged-mind excursions, political awareness made Technicolor, sardonic humor revealing communal truth and a psychedelic call to increasingly imaginative counter-intuitive and counter-cultural response! Why not make the Pentagon float into the ether simply by hippie will and vision? Is there a better, more artful solution?

So I can enjoy George Harrison’s keening “Bangladesh” (“It sure looks like a mess” has to be one of the decidedly least spiritual attempts at profound description of tragedy), Badfinger’s lovely, subtle and naive “Perfection,” ABBA’s sprawling and typically ungainly “Soldiers,” right through to David Bowie’s fabulously scathing “I’m Afraid Of Americans” to Rufus Wainwright’s delightfully jism-drenched “Gay Messiah” and chilling “Going To A Town” to even the Dixie Chicks’ “Not Ready To Make Nice”! Protest is fun! I can’t leave out John Lennon’s impeccable “Imagine”; obviously John Lennon is a whole chapter in protest by himself, and I especially adore the critically underrated Some Time In New York City double LP (well, not so much the Elephant’s Memory jam). “Sunday Bloody Sunday”! And “We’re All Water” is just total too genius, in a Yoko Oh No fashion: “There may not be much difference between Richard Nixon and Chairman Mao/If you see them naked!”

I would even dare to assert that my own Fop is almost, in its entirety, an album of protest. Don’t let that scare you! I covered it all up with loads of strings, production whirligigs, hoodwinks and doodads. I’m not ready to be a dry Woody Guthrie medium like Conor Oberst! In fact, looking down the list of songs, only “Stay,” “Blackpool Lights” and “My Body It” seem legitimately free of slanted, pinko, lefty, homo content.

So in this little treatise, I’d like to touch on two songs that I briefly sideswiped in my “Weepers” post, because they’re not only weepers, but they are what I regard as masterpieces of protest: “Let’s Get Together” and “Morning Dew.” The songs are kind of diametrically opposed, although “Let’s Get Together” has what one might consider the sappiest, most hippy-dippy chorus ever: “Come on, people now/Smile on your brother/Everybody get together/Try and love one another right now.” The verses tingle with a strangely fatalistic, almost biblical poetry and a stately, hymn-like melody that moves me every time I hear the song and might almost make one believe that the call to universal love in the chorus is achievable. Most of the many versions of this song almost involuntarily seem to channel this dreamy, otherworldly, almost bewitching seduction into the pathos of attempting to be loving in a world for which love is not a philosophy of comportment but merely a lifestyle enhancement. It seems every protest song ever written drifts through the streams of melody like pale apparitions at a séance. So when the singer finally says, “You hold the key to love and fear all in your trembling hand/Just one key unlocks them both/It’s there at your command,” it really feels like some sort of devotional revelation. There is the answer, and it’s so very simple. It’s given to you for free on the wings of this gorgeous melody. Why not take the communion?

Attributed variously to Chet Powers, Dino Valente or Dino Valenti and known variously as “Let’s Get Together” or “Get Together,” the song has been recorded umpteen times with way-better-than-average success of translating into a strange, compelling and usually moving vehicle for whomever tackles it. It’s sad that the author did not get to participate in this glory: he apparently sold the publishing rights to Frank Werber, manager of the Kingston Trio, in 1966 to raise money for a legal defense against a drug bust.

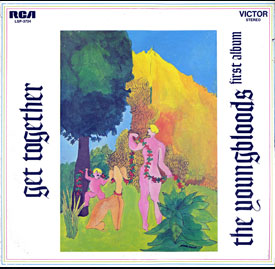

I was first introduced to the song by the Youngbloods’ lovely version and of course had Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, which included a cover of the song. The song even survives the Stone Poneys’ oddly militant, piano-based interpretation that robs the song of the usual chiming Byrds guitar chords used in most covers, and Linda Rondstadt’s hectoring vocal veers a little toward Valley girl, although their recording contains some wonderfully ominous contrapuntal bass.

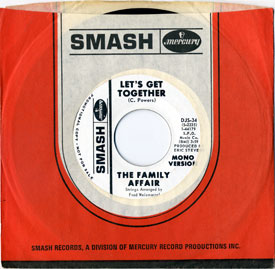

In any case, my library also contains versions by We Five, the Rainbeaux, H.P. Lovecraft, the Leaves, Bonnie Dobson, the Sunshine Company, Chad Mitchell, Carolyn Hester, the Art Gallery, Smith, the Cryan Shames and the California Poppy Pickers! I’m including a version for download by the Family Affair that is the most unlikely combination of powdered-sugar bubble-pop and corporate guitar rave-up. (The record’s been out of print and unavailable for so many years, I hope it’s legal!)

In an odd way, “Morning Dew” is the polar opposite of “Let’s Get Together.” If “Let’s Get Together” is Shakespeare, “Morning Dew” is a heartbroken wail of Gertrude Stein. The lyrics are so reductively minimal and repetitious, as is the melody; it’s like a mantra of melancholy! The saddest thing about “Morning Dew” at this point is that in the Jetsons’ world we were promised for the last say, oh, 40 years, its topic should have, by now, seemed woefully archaic, and the song itself would have become a laughable archaeological anomaly that only students obsessed with the distant past would find campy and humorous resonance in. Unfortunately, it now seems more au courant documentary than nostalgic piffle. As with the more leaden but still occasionally lovely “What Have They Done To The Rain?” (especially in Marianne Faithfull’s Catholic-school-girl-quaver version), the fact that radioactive particulates may accompany the changes in weather to hasten the end of absolutely everything seems less fanciful and more inevitable than ever, given the recent tragic happenstances in Japan. Please, let’s not even go to Nâzım Himet’s “I Come And Stand At Every Door”—the horrific visitation by a ghost child rendered burnt shadow by the atomic blast at Hiroshima (“When children die, they do not grow/Death came and turned my bones to dust/And that was scattered by the wind.” The Byrds and I have actually covered this song already!) I need to keep my tears in check! So let’s stick with the magically moving minimalism that is “Morning Dew.” Basically, all it states in its highly edited format is, “We’d like to enjoy the world, but we can’t, because it’s doomed.” Um, like, the truth! To go from “Walk me out in the morning dew, my honey/I can’t walk you out in the morning dew today” to “Thought I heard a young man crying today/You didn’t hear no young man crying today/You didn’t hear no young man crying at all” is the most rarified, distilled haiku version of apocalypse I’ve ever known.

It suffers from another troubled-songwriter conflict. Though the peculiarly laborious and lead-footed Bonnie Dobson wrote the song, Tim Rose recorded a version of it that brought it to early prominence and diabolically claimed co-authorship. It is also blessed with an anomalous fluidity in the lyrics; in almost every version, some part of the lyrics, be it the subject or the object, has been changed slightly. In fact, that makes it essentially a “folk song” in the tradition of handing down a musical history through the performers, much more than, say, a Bob Dylan song, where the words are considered sacrosanct. It feels more like a tribal legend than a “songwriter” accomplishment. And it is that expansiveness of purview that makes it hymnal: It addresses the very base experience of mortality, willfully distorted by mankind’s cavalier disinclination to witness or acknowledge his own ugly footprint.

I’m so moved by so many versions of this song, from the Jeff Beck Group’s version with a practically fetal Rod Stewart taking the lead vocal (complete with bagpipes and some bad vamping at the end) to Lulu’s heartfelt yet soulful frenzy, which shouldn’t work at all, but does, hauntingly, beautifully. Pre-Deep Purple Episode Six? Check. Even Devo attacks this minimal but moving construct!. This song is so magical that it can actually withstand Nazareth’s unfeeling pomp-rock misappropriation! I have also got in my library versions by the End, Nova Local, Cal Tjader, Group Therapy, Lee Hazlewood, the Damnation Of Adam Blessing and Salena Jones; this is a song that inspired loads of artists to revisit their muse with a huge soulful questioning, “Why?”

Witness the Human Beans’ (unexpectedly lovely) version, the pre-Allmans, hippy-dippy, 31st Of February’s version, some weird ’80s country/backwoods conglomerate called Blackfoot that sounds like a country Simple Minds with a completely inappropriate “yow!” midsong. Even village elders Procol Harum addressing the composition in their dotage. Despite any untoward scat singing, the song survives intact: an unassailable hymn to loss, foreboding and man-made apocalypse rendered in less than three chords and a minimal poetry that Patti Smith will die while envying. Perhaps my current favorite is the amazing Jackie Trent and Tony “Petula Clark” Hatch version, because it includes an unlikely sitar that inscrutably seems perfectly apt with their corporate psych stylings! As “White Bicycle” Tomorrow might say, “Revolution! Yeah!”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NM3-h3NTpBY

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AWQEivI9ph4

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Ney6LlaUI8

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u1uMmdfvWyg

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K_7RwoBTDss