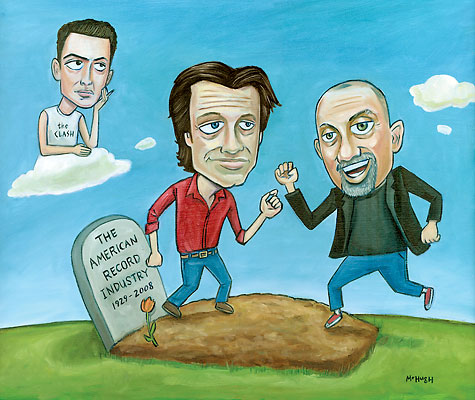

It’s so very punk to want to slam dance all over the grave of the American Record Industry (b. 1929 – d. 2008). Good riddance to The Man. Let us gob on the memory of all those tone-deaf A&R men, greedy suits, house producers, misguided promotions foofs and slick payola palm-greasers. Let the mp3 rule, give the artist the power, long live musical freedom!

It’s so very punk to want to slam dance all over the grave of the American Record Industry (b. 1929 – d. 2008). Good riddance to The Man. Let us gob on the memory of all those tone-deaf A&R men, greedy suits, house producers, misguided promotions foofs and slick payola palm-greasers. Let the mp3 rule, give the artist the power, long live musical freedom!

At this year’s induction ceremony for the Rock and/or Roll Hall of Fame, no less a rebellious iconoclast than Billy Joel (80 million records sold) introduced musical freedom fighter John Mellencamp (28 million units moved) with a note of triumph: “Congratulations, John! You outlived the record industry!”

So yes, let’s grave dance over the disease-riddled and venal corpse of the entirely despicable American record industry. Cause of death: a lethal overdose of its own greed and failure to notice those technological advancements speeding in its lane. But be careful what you wish for, because we owe the vile and disgusting record industry a lot more than it’s popular to admit. Start with the most basic contributions. Major labels gave you Elvis Presley, Little Richard, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, the Kinks, the Who, Jimi Hendrix, the Grateful Dead, Led Zeppelin, Neil Young, David Bowie, Bruce Springsteen, the Ramones, the Clash, Tom Petty, U2, Pearl Jam, Radiohead, the Strokes …

You get the point.

No sane person, and I believe I’m included in that subgroup of humanity, would claim that major record labels didn’t foist more bad product on us than good. But there was a certain value in having a structure in place that more or less served to discover and develop talented musical artists.

Let’s use Major League Baseball as a handy, in-season analogy. You go to a big-league game, and you’re assured of a certain level of performance. You trust that you’re seeing the very best players in the world—not because baseball as an institution isn’t deeply flawed (it is, trust me), but because teams spend countless hours and millions of dollars scouting, signing and developing talented players. Some go undiscovered. Some don’t get that one chance. Some turn out to be not quite as good as expected. Some make grown men rise out of their seats, beer sloshing over the rims of plastic cups, to scream, “You suck!”

You can go to a minor-league game, and it might be competitive, but you know you’re not looking at the best possible players. You can go to a sandlot game and be entertained and enchanted by the enthusiasm on display, but there’s no resemblance to the talent level at the minor-league park, let alone the major-league stadium.

At their best, major labels really did go out, scout talented musicians, record them, promote their releases and underwrite their tours. A visionary like Ahmet Ertegun at Atlantic or Seymour Stein at Sire could recruit a whole roster of artists worth hearing. You might even buy an album just because it came from a label whose other bands were mostly good.

OK, fine, that’s the most elemental reason to remember the era of the major labels fondly. And I reiterate that those positives were counterweighted by any number of negatives: dishonest, exploitative contracts, pressure on artists to be more commercial, the abandonment of worthy artists who took too long to find an audience, the REO Speedwagon catalog. All true, all true.

But even in the negatives, there were positives. This is where the logic gets a little harder to follow, so bear with me. The short version goes: Without a Them, who is the Us? Case in point: The Clash’s “Complete Control,” from 1977, was written specifically because the band was pissed off that CBS Records released the song “Remote Control” as a single against the group’s express wishes. Not only would “Complete Control” not exist if the muckety-mucks at CBS weren’t a bunch of jagoffs, but it’s a better song than “Remote Control.” At a time when critics were calling the Clash sellouts for signing with a major label, the band was inspired to defend itself by writing an angry condemnation of that very label: “They said, release ‘Remote Control’/But we didn’t want it on the label.” And later: “They said we’d be artistically free/When we signed that bit of paper/They meant, we’ll make lots of money!/And worry about it later.”

The beauty, of course, is that “Complete Control” came out as a single. On CBS Records. The scumsuckers in suits didn’t care about being ripped in song. They just wanted to sell more Clash records.

Seven years earlier, the Kinks released a whole album, Lola Versus Powerman And The Moneygoround, about their conflicts with the vultures at record companies. The central theme of “The Moneygoround” sums it up: “Do they all deserve money from a song that they’ve never heard? They don’t know the tune and they don’t know the words, but they don’t give a damn.”

After signing over the rights to his Creedence Clearwater Revival songs—just imagine what they’re worth—to Fantasy Records executive Saul Zaentz, John Fogerty wrote the blistering “Zanz Kant Danz” (“but he’ll steal your money,” goes the lyric) and put it on his Centerfield album in 1985. Zaentz sued Fogerty, who changed the title and lyrics of the song on subsequent pressings.

No evil bastards at the record company, no Lola Versus Powerman And The Moneygoround, no “Complete Control.” Who knows? Maybe if he didn’t need the money, Fogerty never makes his mid-’80s comeback and records “Centerfield,” a song that will forever haunt baseball stadiums.

Rock ’n’ roll needed something to rebel against. Whether that was a stifling ’50s mainstream culture, a disastrous war in Vietnam or the record industry itself was immaterial. Without an evil, oppressive establishment, rebellion is just so much jerking off. The tension generated by creative artists working for inherently life-sapping monolithic corporate shitmongers informed the careers of some of the greatest musicians of the rock era: Neil Young, Tom Petty, Paul Westerberg, Kurt Cobain, Eddie Vedder.

And you don’t have to go back to the ’60s or ’70s or ’80s, either. Would Wilco’s Yankee Hotel Foxtrot have made as big an impact if Reprise had just gone ahead and released the damn thing? It would’ve been precisely the same album, with exactly the same terrific songs and sounds. But it wouldn’t have been a cultural touchstone if Reprise head David Kahne had ears. One of the best albums of this decade, the Wrens’ The Meadowlands, was largely inspired by that band’s unfortunate dealings with a would-be record mogul.

It’s just a hunch, but I don’t expect there to be any great songs about illegal downloads. The artists of the next decade will basically be playing in the sandlot, hoping someone notices they’re major leaguers. There won’t be any contracts to bitch about.

Resume the grave dancing.

—Phil Sheridan