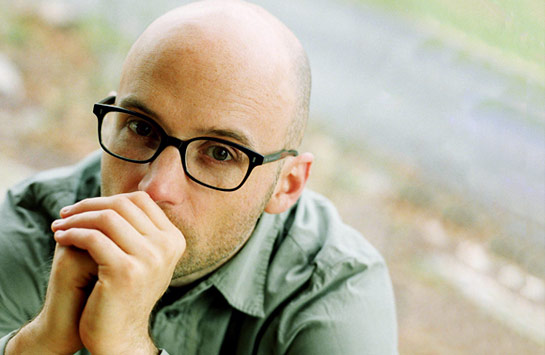

Like fellow one-named, slightly built, narcissistic workaholics Prince and Beck, Moby (the most charming and humanistic of that club) has slowed his output in the new century. Almost three years have passed since he released 18, a bloated album that still managed to soak up a wave of critical backlash. Moby’s new, sample-free Hotel (V2) is scarcely slimmer, even without its bonus ambient disc. While the first half of the record is stripped-down and kinetic, much of the second half—the primitive, sex-with-an-Atari-2600 burble of “I Like It,” the Vangelis-flying-too-close-to-the-ground “Homeward Angel”—never comes into focus. But even on 1995’s Everything Is Wrong and 1999’s Play, Moby’s industry trumped his inventiveness. His sense of economy—not no-wasted-gesture economy but rather bargain-basement, wow-it-has-a-shitload-of-tracks economy—holds up here as ever. Moby’s bang-for-the-buck philosophy seems tied to his relationships with various commercial users of his music. He revealed as much in a recent entry in his online journal, which cited childhood poverty as a possible reason for his shrewdness. Does the guy get a bad rap for issuing more licenses than a Las Vegas justice of the peace? Even he doesn’t know, and Moby is an expert on himself first. Hotel is another chapter of Moby’s meta narrative on the succor he finds in, well, being Moby. He can check out any time he likes, but he would never leave.

Like fellow one-named, slightly built, narcissistic workaholics Prince and Beck, Moby (the most charming and humanistic of that club) has slowed his output in the new century. Almost three years have passed since he released 18, a bloated album that still managed to soak up a wave of critical backlash. Moby’s new, sample-free Hotel (V2) is scarcely slimmer, even without its bonus ambient disc. While the first half of the record is stripped-down and kinetic, much of the second half—the primitive, sex-with-an-Atari-2600 burble of “I Like It,” the Vangelis-flying-too-close-to-the-ground “Homeward Angel”—never comes into focus. But even on 1995’s Everything Is Wrong and 1999’s Play, Moby’s industry trumped his inventiveness. His sense of economy—not no-wasted-gesture economy but rather bargain-basement, wow-it-has-a-shitload-of-tracks economy—holds up here as ever. Moby’s bang-for-the-buck philosophy seems tied to his relationships with various commercial users of his music. He revealed as much in a recent entry in his online journal, which cited childhood poverty as a possible reason for his shrewdness. Does the guy get a bad rap for issuing more licenses than a Las Vegas justice of the peace? Even he doesn’t know, and Moby is an expert on himself first. Hotel is another chapter of Moby’s meta narrative on the succor he finds in, well, being Moby. He can check out any time he likes, but he would never leave.

How long did Hotel take?

On and off, a year and a half. When I first started making it, I wanted to make a very degenerate and frivolous disco record.

Like Beck’s Midnite Vultures?

I love Beck, but I can’t say I was a big fan of that record. If he’d made it under a pseudonym, it would have been a much better record.

What happened after you gave up on disco?

I wanted to make a ballads record, so I wrote 30 or 40 ballads. But even though I’d still love to do it, I decided this wasn’t the time, so I started over again.

You seem to record fewer experiments, in favor of what might now be called straight-up Moby albums.

It’s a pretty remarkable privilege when people actually pay attention to what you do. There’s a part of me that wants to go play speed metal, but there’s a part of me that’s altruistic about the people who pay attention to what I do. I really like the idea of making a record that plays a part in someone’s life. There are albums that are warm and altruistic—Bryter Layter by Nick Drake or Closer by Joy Division—very inviting, warm records.

The word “warm” doesn’t leap to mind when you say Joy Division.

It’s about emotional response. Prayers On Fire by the Birthday Party is a grating record, but it’s like a party. And even though it’s a big, obnoxious party, you’re still invited to it. Scott Walker’s Tilt is smoother, but it’s like, “This is my record. You can stand over there, but you’re not invited.”

Do you have an emotional response in mind for Hotel listeners?

It’s not premeditated. The ultimate litmus test is, “How do I respond to it emotionally?” My hope is that it will elicit a similar reaction in other people. There are some people who are good at looking at a demographic and knowing how that group will respond. I don’t know if that’s one of my skills.

Do you think of your audience in subgroups that match the genres in which you record?

I’ve made so many different types of records that subgrouping would lead me to a core demographic of 11 people. I’ll be at a party and people will say, “I got your first record,” and they mean Play.

Does that bother you?

Actually, it embarrasses me.

Why?

Because it makes me think that no one heard my first seven records.

It just means that some people who love an album don’t bother to dig into that artist’s catalog.

Music is competing with so many things that it has, for a lot of people, become quite marginalized. I hope it’s shifting. I know for a lot of people, you’d buy a music magazine and you’d read the reviews and you’d file it away. Now the immediacy means that if someone is reading MAGNET, they can go online and find the album 15 minutes later.

Are you ever guilty of marginalizing music yourself?

I have a very busy life, but I’m still cursed with too much free time. I think part of the reason for that is that I have a really hard time getting too enthusiastic about the things most people do. I don’t want to sound arrogant, but I’m envious of people who can kick back, relax and play a video game. Life is short, and anything that can make you happy without hurting other people is a good thing. I work hard, but work is my favorite thing to do. If it’s a Saturday afternoon and I have nothing to do, I’m hard-pressed to think of anything better to do than work.

You wrote in your blog that growing up poor has made you feel reluctant to turn down money—and that you’d never made the connection before.

For some reason, it didn’t occur to me that that would be behind some of my lifestyle habits.

What lifestyle habits?

I go around and turn off the lights and turn down the thermostat at my house. My friends make fun of me. Also, I still have a hard time drinking undiluted juice. We had to make orange juice last as long as possible, and I grew up drinking half water, half juice. It’s hard to change your habits.

Is anything from Hotel licensed yet?

I don’t think anything has been set up. There’s this part of me that worries I’ll regret the licensing. Everything on Play was licensed, but two or three of the shorter songs were licensed to student films. It’s a weird issue, and I understand why people take issue with me. There’s this part of me that sees a lot of double standards, and on the one hand, I don’t feel qualified to talk about it because I sound defensive.

Do you feel pressure, having been so outspoken politically, not to slip up and expose yourself to charges of hypocrisy?

I want to get people to recognize in a compassionate way just how complicated life is. Rigid, polemical ideologues make me uncomfortable. I wear my inconsistencies as a badge of honor. Anyone who purports to lead a consistent life has his blinders on. The tricky part is that I used to be a rigid, polemical ideologue. Until about 1994, I was as rigid and didactic as you can get.

Yet you seem to like being famous.

It’s not so much liking being famous. Fame is like a television in that it has no inherent value … OK, rather than a TV, fame is like a bicycle. It’s only good when it takes you to interesting places.

Maybe it’s more like a car: It breaks down, and it’s not always under your own power.

Yes. And I don’t use fame just for good purposes. Your ego is stroked. It’s nice when an attractive woman at a party talks to you because of your music. When I first started making music, I didn’t think it was possible. As a kid, I resented rock and movie stars on some level because their lives were so fantastic and made me feel inadequate. From the outside, it might seem glamorous to be a public figure. But there are facets that, while they’re not onerous, they’re not glamorous. If being famous were too hard, I would stop.

After a point, though, there’s no way to keep some people from disliking you, whether it’s just because you’re famous or for your politics.

I go on the message boards every couple of days. I’d say half the people on the boards view me with some degree of disdain. I wouldn’t call it a fan site. You would think that going around and trolling my own site would be an exercise in ego gratification. But more often than not, it’s depressing. Sometimes their reasons for disliking me are valid and cause me to reflect on what they’re saying.

Have you ever made a palpable change in your demeanor because of the board?

Sort of. There were a lot of members in the Green Party in 2000, and I took great offense that Ralph Nader was siphoning away votes from Al Gore. I was vitriolic, and I’ve tried to learn since then not to be strident and not to scream.

—Scott Wilson