“I’m not what you think I am,” declares Stephen Malkmus on his post-Pavement solo debut. No, he’s not really Yul Brynner or the King Of Siam. But it’s still a wonderful life. By Jonathan Valania

I’m driving Stephen Malkmus’ car. In America, that’s tantamount to possessing someone’s soul. But wait, it gets better: I’m listening to Slanted And Enchanted—make that Malkmus’ copy of Slanted And Enchanted—and it sounds great as I tool down the sun-kissed streets of Portland, Ore., with the windows down and the stereo up. There’s a parking ticket flapping beneath the windshield wiper—and it bores me. I look around at all the people, and I just don’t care. Not a care, really, in the world. I am, for a moment, Stephen Malkmus, fortunate son. Listen to me, I’m on the stereo.

Actually, I’m driving Malkmus’ girlfriend’s car. Which you would know is even better if you’ve ever seen his girlfriend. Her name is Heather Larimer, and she’s beautiful and bright and 28. She was a cheerleader and she has a master’s degree in creative writing—a major-league summer babe (AOL Keyword: Babia Majora). By the time you read this, you may have already seen her singing in Malkmus’ new band, the Jicks. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s back up.

I’m driving Malkmus’ girlfriend’s car because I’ve come to Portland to find out what it means to be Stephen Malkmus (AOL Keyword: Laconic), and the first thing he wants to do is get a friggin’ battery for his car. It’s a 1989 Acura Legend, and it’s been stranded for months in front of his former apartment up in the rich, old-money part of town. Up here, on this faintly Olympian perch where even modest homes list for $300,000, we sit waiting for the AAA guy. Malkmus, the man Courtney Love called “the Grace Kelly of indie rock,” doesn’t want to be interviewed yet, and it isn’t like I know him from Adam; for that matter, after spending three days with him, I will still not really know him from Adam. Aside from a bit of strained small talk, my first half hour or so in the company of one of indie rock’s most acclaimed wordsmiths is spent in silence, watching him clean out his trunk. A soggy copy of an old income-tax form. A Thin Lizzy album. A rumpled suit bag and battered dress shoes, probably last worn to the funeral of his friend Robert Bingham (author of a collection of short stories called Pure Slaughter Value and heir to a publishing fortune). Bingham died from a heroin overdose in the fall of 1999. “I don’t think he was really that into it,” Malkmus will tell me later. “I think he just tried it with this girl … ” The rest of the thought trails off to protect the privacy of the dead.

There’s a song on Malkmus’ self-titled solo album called “Church On White.” It’s prime Malkmus. He sounds sad-eyed and shattered, and the guitars clang languidly, loping along in figure-eights of resignation and regret. It ends with a tolling passage that closes the lid on the final chorus before flaming out in a wailing-wall guitar solo. If every Pavement song was about thinking, this song is about feeling. “Church On White” is about Bingham. He used to live at the intersection of Church and White streets in New York City.

The AAA guy finally arrives and gets the Acura started. Malkmus wants me to follow in Larimer’s car as we go shopping for a new battery. I fish Slanted And Enchanted out of the glove compartment and pop it in the tape deck as we zigzag through the streets of Portland, visiting five different auto-parts stores before Malkmus finds what he needs. File this under Doing Ordinary Things With Extraordinary People. Make no mistake, Malkmus is extraordinary—some say the finest songwriter of his generation—but he replaces his car battery just like you and me: He has the guy at the car-parts store do it.

That’s about all I can tell you about Malkmus with any degree of certainty. Other than that, you’re on your own. I hung out with him, asked him questions for hours, watched him make music, looked at the records in his collection, the books on his shelves, the magazines on his coffee table. I called his old bandmates and his record company. I even called his dad (great guy, by the way). The facts are all here, but, as with any good Pavement song, it’s up to you to figure out what it all means.

Being Stephen Malkmus is … easy. You’re born upper-middle class in Los Angeles, the son of a general property/casualty insurance agent. You live on Citrus Avenue in the City Of Angels, where the sun shines all the time. When you’re eight, you move upstate to the tony suburban subdivisions of Stockton, where you’ll live out your formative years. You meet this kid named Scott Kannberg on your soccer team. You play wing. You learn to play guitar by aping Jimi Hendrix on “Purple Haze,” which features this tricky E chord. When you finally pull it off, you realize you can now play the guitar. You spend your puberty at all-ages punk shows. You even start a punk-rock band called the Straw Dogs, which sounds like a cross between the Adolescents, Wasted Youth and Dead Kennedys, as was the style at the time.

At age 18, you depart cross-country for the University of Virginia, because it’s the best school that accepted you and, besides, your old man went there. You have the distinct feeling you were one of the last students accepted because you’re assigned a room in the basement of the freshman dormitory, which you call a “ghetto for all the dumb kids.” You don’t complain, because even though you fill out the New York Times crossword puzzle in ink, you don’t test well and you only scored 1180 on your SATs. After a couple of years, you declare a major in history because you get the best grades in those classes._You meet David Berman, who will one day be regarded as one of the finest poets of your generation. You will one day make albums with him under the name Silver Jews. (You aren’t Jewish.) You will also meet a super-nice guy named Bob Nastanovich, who will one day talk you into co-owning a racehorse named Speedy Service with him. Who knows, you might even ask him to join your next band if you ever get around to starting one. The three of you become DJs at the college station and sit around drinking beer while raiding the deepest depths of the record stacks: Can, Chrome, Swell Maps, the Fall. These records will serve you well in due time. So well, in fact, that the Fall’s Mark E. Smith will one day curse you in the pages of Q magazine for riding his style to the bank. If someone told you this back in college, you would’ve never believed it.

You record an album under the band name Lakespeed, which even you have to admit sounds a little too derivative of Sonic Youth and the other college-radio superstars of the time. You send it around, but no label is interested. After graduating with a respectable 3.2 grade-point average and not even a vague clue as to what you want to do with your life, you go back to Stockton. You team up with Kannberg, because he’s the only one of your acquaintances who still lives there. He’s learned to play guitar. You make up aliases for each other: You call him Spiral Stairs, he calls you S.M. You record some songs for a seven-inch single you purposely try to make sound really bad, like Television Personalities or Chrome or Pere Ubu. Later, people will call this “lo-fi.” On the day you record, you’ll learn later, a grisly mass murder happens downstate, which is odd because you’ve already decided to call the seven-inch Slay Tracks.

You leave all the pedestrian details of pressing the singles and mailing them out to zines and record labels to Kannberg—who decides to call the project Pavement—and head out on a year-long backpacking trip across Europe. You’ll also visit Egypt, Jordan and Iraq, where you’ll hike out to the intersection of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, which, in the Bible, is called Eden. When you get back, you’re amused to learn Slay Tracks has been well-received. You record another single called Demolition Plot J-7 and follow it up with a 10-inch called, rather archly, Perfect Sound Forever. The buzz builds. You move to New York to live with good ol’ Nastanovich. You and Berman get jobs as security guards at the Whitney Museum Of American Art, and to fill the endless ennui of standing for hours babysitting some of the greatest artistic achievements of Western culture, you make up an album’s worth of songs in your head.

Spending Christmas back in Stockton with your family, you record these songs. You call it Slanted And Enchanted. It will change music. It will change people’s lives. It will change your life. You’ll become the slacker prince of indie rock and, as befits the title, you’ll never have to work another day in your life.

That’s the beginning of Pavement (AOL Keyword: Irony); as the middle is well-documented, we’ll talk about the end.

“I wasn’t particularly proud of Pavement at that point,” says Malkmus, recalling the drudgery of recording the band’s final album, 1999’s rather dismal Terror Twilight, and the joyless tour that followed. “I thought it had gone on too long. I wish it would have ended after, like, two records or something. It’s not a bad band to be in, don’t get me wrong. We had been talking about it not being what it should to people for some time. There was an edge to it that was not as heartfelt as it should be to be going out and shoving shit down people’s faces.”

Did you feel that way, or did the other people in the band feel that way?_“You would have to talk to individual people,” he says. “I’m sure that there is a part of everyone that would like to keep it going, because anything they do after that isn’t going to be any bigger. It was a pretty successful run. You want to hold on to that. But I hope everyone realizes that it was the right time to pull the plug and end on an OK note … I made it clear to people in many ways that there was no way I could make another record the way we made records. Making the Silver Jews album (1998’s American Water) was another thing that made me realize that there’s such a better way to be making records, and I knew I could do it. We did that in four days and that was a breeze, and it was such a better record than [Terror Twilight]. I mean the performances, maybe not the songs or the mix, but the performances were much more inspired. I realized I could do that. I didn’t need to settle for uninspired performances.”

When was it official Pavement was over?_“It’s never official, I guess. Anyone that’s asked me for the last year and a half, I’ve said it was over. So I guess a year and a half.”

After the tour for Terror Twilight?_“Before that, even—during it. I never made a formal announcement and nobody asked me in an interview, so we never said anything. I would have liked to have maybe made it more official, but it wasn’t a pressing thing on my mind, and nobody else in the band wanted to do it. So I was like, ‘I’ll just wait until my solo album is out and I have to talk to people anyway for promotion.’ I can kill two birds with one stone instead of having some meaningless media thing last March.”

Do you ever write songs that reveal something about yourself?_“Not really. I’m always commenting or assuming voices about lives that would be interesting to me. I’m not particularly interested in my own feelings or my own struggles, so I wouldn’t write a song about them. But anything you write is a reflection on you, so if you are into being non-revealing, it shows your personality. So I never feel like I’m selling people short.”

What do you think about the way writers characterize you as being cold and aloof?_“It’s never been a problem. Just about every song I like is the same way. The Velvets are always singing about somebody else. Van Morrison is singing about Crazy Face or whatever, and it doesn’t have anything to do with him. People think he’s soulful.”

Do you feel naked going out there without Pavement and just your name up there in lights?_“No. I really don’t care at this point. I’m a big boy and I have my posse. I think it’s gonna be fine. I wouldn’t do it this way if I wasn’t over any deep, stoner-paranoia thing.”

The next night, I’m sitting in a Portland bar with Malkmus and his Jicks: drummer John Moen, bassist Joanna Bolme and back-up singer Larimer. It’s a running joke around Portland that Larimer is Malkmus’ Yoko Ono, in part for her singing style, which, shall we say, has a very casual relationship with the notion of being in key. But she’s much more than just the candy cane on Malkmus’ tree; she’s probably given him the confidence, if not the itch, to strike out on his own. That’s a beautiful thing for one human being to pass along to another.

(This is the part of the story that’s in parentheses. It’s just a theory, and Malkmus, notoriously reluctant to reveal himself in his songs, would never admit this, but I think the song “Jenny & The Ess-Dog” from his solo album is really about their relationship. Some of the names have been changed, but you don’t need a secret decoder ring to figure out who the “S” Dog is. Even though the facts have been disarranged—“She’s a rich girl, he’s the son of a Coca-Cola middleman”—the song has the same vibe Malkmus and Larimer give off when they’re together. It sounds like summer, like falling in love. It’s the catchiest song he’s written since “Cut Your Hair.”)

Moen has pulled drum duty for the Fastbacks and Dharma Bums. He has his own band called the Maroons, which, he says, “doesn’t get off its ass much.” At 32, he looks like a regular-joe version of actor Greg Kinnear, exuding the same disarming niceness and likability. They used to call guys like him “happy go lucky,” but nobody is this happy or lucky anymore. Moen once made his living as a tree surgeon, but “it just didn’t go well with rock ‘n’ roll,” he says. “You gotta be alert when you are running a chipper and climbing trees with a chainsaw in your hand.” Moen owns exactly two Pavement albums: Wowee Zowee and another one he can’t quite remember. “I’m a poor record buyer,” he says, as if his casual Pavement fan status somehow undermines his legitimacy as Malkmus’ drummer.

Moen met Bolme when they played together in one of the latter incarnations of the Spinanes. Before that, Bolme was in Calamity Jane. “It was pre-riot-grrrl, all-girl punk rock,” she says, adding she first heard Pavement on tour with Calamity Jane, listening to Slanted And Enchanted over and over in the tour van. Until recently, she played bass in the Minders, a Portland psych/pop outfit with Elephant 6 connections. Oh yeah, one more thing (and she’ll likely want to strangle me for printing this): She was, on and off for years, the love of Elliott Smith’s life. It’s a safe bet many of Smith’s songs are, in some way, about her. Bolme met Malkmus when the Spinanes’ Rebecca Gates brought her around to his place to play Scrabble.

The next day, the Jicks are rehearsing in the basement of the house Malkmus shares with Larimer, a charming Victorian two-story skirted with a spacious yard. It’s located in a much more modest neighborhood than his last digs. Malkmus is looking to buy, but he still hasn’t found what he’s looking for.

The Jicks have yet to play a proper gig, and they’re a little nervous about their impending live debut in New York. The basement is small and cramped and barely fits the band, so I sit alone up in the living room, listening through the heating vent. I hear Malkmus explaining to touring keyboardist Mike Clark exactly which sounds from the album he’ll be expected to play and which ones will be sampled from the record—which turns out to be quite a few.

“That’s cheating,” says Clark.

“That’s OK,” says Malkmus.

As the Jicks run through the material from Malkmus’ solo album, I visually catalog the contents of the living room. On the turntable: Swaddling Songs by Mellow Candle, an obscure, late-‘60s Irish psych/folk outfit that sounds a bit like Jefferson Airplane. According to Malkmus, an original copy of Swaddling Songs fetches $900. (He has a less-valuable later pressing.) Sitting on deck: Fairport Convention’s What We Did On Our Holidays, R.E.M.’s Fables Of The Reconstruction, Thin Lizzy’s Johnny The Fox and an album of Greek cooking tips. Stacks and stacks of precious vinyl sit nearby. On the bookshelf: In Touch by Paul Bowles, Force Majeure by Bruce Wagner, Collected Poems by Philip Larkin, Vectors And Smoothable Curves by William Bronk, Mexico City Blues by Jack Kerouac and a book about Japanese film directors. The shelves are full, and there are still boxes and boxes of books waiting to be unpacked. On the refrigerator hangs a Christmas card from Sleater-Kinney’s Corin Tucker and her husband, Lance Bangs, who directed two of Pavement’s videos. Inside the card is a photocopy of Tucker’s sonogram above the words, “From Corin & Lance And The Little Guy.” There are a few Steve Keene paintings scattered about the house, the collector’s edition of Scrabble and an eight-track player.

A couple hours later, practice ends and everyone sits around the living room sipping herbal tea. Malkmus is ridiculously attired in a misshapen Stetson (not unlike the one Hoss wore on Gunsmoke), an Evergreen T-shirt, sweatpants, beige running shoes worn like slippers and ugly brown-tinted shades that even David Hasselhoff couldn’t pull off back in the Knight Rider days. Larimer gives him shit for the sweatpants.

“This is my practice outfit,” Malkmus says with mild defensiveness. “(Black Flag guitarist) Greg Ginn always wore sweatpants, and he looked good.”

Malkmus plays DJ: Mellow Candle’s “Silversong” (which he wants the Jicks to cover), Sparks’ “Wonder Girl,” an obscure ‘60s L.A. group called Touch and Buzz Martin (a local logger who made two country albums of modest kitsch value). Malkmus and Larimer have been taking yoga classes, and he shows off some moves. He assumes a perfect Tree Pose, then The Rabbit, and then he curves his body into a little donut hole.

Malkmus is 34, but he’s just now getting around to looking late 20s. He still dresses like an untucked tennis pro. If he was a car, he would be a Volvo with ancient plates. He’s still an inside joke. On record, Malkmus sounds like he’s talking when he sings, but he’s actually singing. His speaking voice is a few notches flatter in affect and even more devoid of emotion. He’s nearly impossible to read—“inscrutable” is Webster’s word for it—which is only compounded by his habit of looking away from you when he speaks. If you look up “laconic” in the dictionary, in some editions you’ll see his picture next to the definition: “concise to the point of seeming rude or mysterious.” He lolls about contentedly on the floor, but when he becomes aware I’m taking notes, he spins the conversation into verbal blind alleys. He gets out a book by Ronald Firbank.

“He wrote a book in the ‘20s called Prancing Nigger—he shouldn’t have done that,” says Malkmus, with an impish grin. “W.H. Auden said he judged people on the basis of whether or not they liked Firbank. I have to decide whether or not I like him.”

Are you a big fan of W.H. Auden?

“Not really,” he says dismissively, getting up to put the Psychedelic Furs’ debut on the turntable.

Being Stephen Malkmus is … hard to figure out when you’re the guy writing this article. Malkmus really isn’t much help. So I ring up the Pavement guys. Bassist Mark Ibold doesn’t return my phone calls. The wife of drummer Steve West calls to say he’s on tour in Europe with his band Marble Valley and probably won’t be available. Original Pavement drummer Gary Young, who recorded all the band’s stuff up until 1994’s Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain, agrees to talk but isn’t home when I call at the agreed-upon time; his wife will call back to say Young is out of town and won’t be available for comment.

Good ol’ Nastanovich—Pavement’s percussionist, Moogist and designated shouter—is happy to talk. He’s remained friends with Malkmus and will be road-managing the Jicks, a duty he performed for Pavement’s Crooked Rain tour. “I earned the nickname Harsh Harold,” he says. “I was kind of a slave driver.” Nastanovich (AOL Keyword: The Nas) could see the end of Pavement coming a long way off. He’s just surprised it lasted as long as it did.

“Each tour would end, and it would pretty much be the end of the band,” he says. “And then we would regroup again 10 months later. After the Terror Twilight tour, it was left that it would be on hiatus for a long, long time, if not forever. It was left that we might get back together one day, but it was gonna take a lot longer than just 10 months. I have no regrets. We were an extremely fortunate rock band that got to do things our way and still have a career. It was a great way to spend the ‘90s.”

So, Bob, who is Stephen Malkmus?

“An unusually talented guitarist and songwriter,” he says. “I remember back in college being pretty confident that I was friends with one of the best songwriters in the country in Malkmus and one of the best writers in America in Berman. Not that they both weren’t huge pains in the ass.”

Thanks, Nas.

Kannberg answers the phone, and although he’s a little wary at first, he agrees to talk. Kannberg (AOL Keyword: Spiral Stairs) is finishing up work on the debut album by his band the Preston School Of Industry. Kannberg first met Malkmus in the third grade, though they wouldn’t actually become friends until after high school when they bonded over a mutual love of British post-punk. His first impression of Malkmus: “He was the bratty rich kid.” I ask him how he learned Pavement was breaking up.

“Six months after the Terror Twilight tour, Steve sent me this email that he wanted me to put up on the Pavement website saying that we broke up,” says Kannberg. “I was like, ‘Oh, we broke up!?’ I spoke with the other guys, and they were surprised. Steve’s whole thing was, ‘They should have known. They should have read between the lines.’ I told Steve that I wouldn’t put [the break-up announcement] up on the website until he talked to the rest of the band first. He never got back to me … I’m proud of what we did with Pavement. The way it ended left a bad taste in my mouth, but I’ll get over it. I want to stay positive and leave the negativity to Steve Malkmus.”

Kannberg calls me a week later, concerned he came across as bitter. Not to worry, Scott.

I phone Malkmus’ dad, Stephen Sr., knowing full well Junior probably won’t be pleased. The elder Malkmus is, understandably, very proud of his son, even if Pavement’s music isn’t exactly his cup of tea. “He’s so darn talented,” he says.

How would he describe his son?

“Kinda quiet, very intellectual. He thinks about things a little differently than other people in his line of work.”

Yes, I suppose he does.

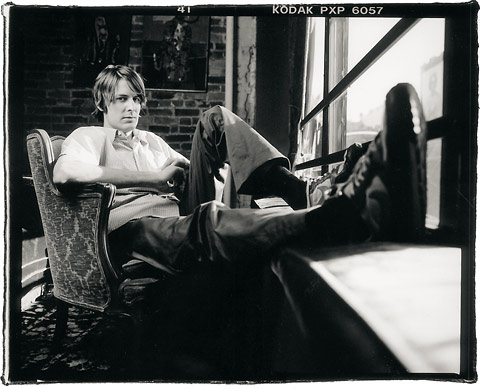

Next, I call Chris Lombardi, who along with Gerard Cosloy, owns and operates Matador Records, Malkmus’ label. Yes, it’s true, Lombardi says, that Matador dissuaded Malkmus from calling his new project the Jicks, at least on the album cover. “We kind of freaked out,” says Lombardi. “It was going to be this Carter Family thing: Stephen Jick, Joanna Jick, John Jick. I was like, ‘Stephen, you have to understand that people know who Pavement is, but they don’t necessarily know who Stephen Malkmus is. And they certainly don’t know who the Jicks are.’ I mean, if you listen to it, it’s Stephen’s record. He’s exuding this new confidence, you can see it in the cover photos. In the old Pavement photos, he’s hiding behind the other guys half the time. He’s stepping out.”

And just who is Stephen Malkmus?

“That’s a tough one,” says Lombardi. “He’s a cryptic guy, to start with. One of the smartest and most talented people I know. He’s confused me many times.”

Finally, I email Berman. Sensing the direct approach is getting me nowhere, I send him this question: What epitaph should be written on Malkmus’ headstone, god forbid?

Berman emails back: “Being dead’s OK. It’s alright. I don’t mind much.”

It’s a few weeks later, and Malkmus’ Jicks are making their New York City debut at the Bowery Ballroom. The show sold out almost as soon as it was announced. The crowd is heavily weighted with industry insiders, media types, Matador friends and family, various hipster hangers-on and guys who are the coolest dudes in their dormitory. There are also some in the audience who would like nothing more than to be able to report that indie rock’s emperor has no clothes. By now, the critics’ verdicts on Stephen Malkmus have begun to come in, and the consensus is a solid B-plus from anyone who’s been paying attention since Slanted and four-star hyperbole from anyone who’s just trying to look hip with “the kids.” Ibold is in the crowd, as is Jon Spencer. Matador’s solution to the brand-name recognition problem presented by Malkmus going solo is to hand out T-shirts to everyone in attendance that read: Who The Fuck Is Stephen Malkmus? Good question. By this point I, too, have been putting the “fuck” in there whenever I ask it.

Malkmus elects to begin the set with “Jo Jo’s Jacket,” and maybe it’s just opening-night jitters, but his Jicks look and sound like extras in the movie adaptation of the sequel to Pavement. Though the crowd responds warmly, Malkmus asks that the audience keep in mind that this is their first show. Someone semi-seriously calls out “Judas!” which, like everything Malkmus/Pavement-related, seems to come with those little quotation-mark hand gestures attached, as in, “This is sort of my generation’s Dylan at the Royal Albert Hall, but not really.” I ask the stranger next to me what he thinks.

“Pretty good,” he says, “although the chick singing is kind of a distraction.”

Actually, that’s Malkmus’ girlfriend.

“Right on! I’m all for having a girlfriend that looks 17!”

Rumor has it Elastica’s Justine Frischmann was supposed to play guitar with the Jicks tonight, but it didn’t work out. Malkmus and Frischmann have been “just friends” for years. The Ess-Dog always stayed at her London flat whenever Pavement was in town. “I remember one morning we came by to pick him up,” said Nastanovich. “He comes walking out, and our roadie says, ‘It looks like she did his hair with her thighs.’” You almost have to wonder if she didn’t befriend Malkmus just to piss off Blur’s Damon Albarn, her ex-boyfriend and an avowed Pavement fan. I think back to the first night I met Malkmus for this story, in Seattle on New Year’s Eve, and how he was wearing a Mogwai T-shirt that read: Blur Are Shite.

Truth be told, the Jicks could use a second guitarist right about now. With his voice and guitar pushed high in the sound mix, Malkmus seems, at first, a little naked without some Pavement to surround him, diffusing attention and spreading out the blame. But Malkmus has always cloaked himself in good tunes, and by the time the Jicks get to “Church On White,” a song with miles and miles of style, he seems impeccably attired. Adorned. Imperial. Like the Grace Kelly of indie rock.

It’s then I realize that being Stephen Malkmus … is, well, something only he can do. Something he has to do all by himself.

2 replies on “Stephen Malkmus: Being Stephen Malkmus”

[…] You leave all the pedestrian details of pressing the singles and mailing them out to zines and record labels to Kannberg—who decides to call the project Pavement—and head out on a year-long backpacking trip across Europe. You’ll also visit Egypt, Jordan and Iraq, where you’ll hike out to the intersection of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, which, in the Bible, is called Eden. When you get back, you’re amused to learn Slay Tracks has been well-received. You record another single called Demolition Plot J-7 and follow it up with a 10-inch called, rather archly, Perfect Sound Forever. The buzz builds. You move to New York to live with good ol’ Nastanovich. You and Berman get jobs as security guards at the Whitney Museum Of American Art, and to fill the endless ennui of standing for hours babysitting some of the greatest artistic achievements of Western culture, you make up an album’s worth of songs in your head. Spending Christmas back in Stockton with your family, you record these songs. You call it Slanted And Enchanted. It will change music. It will change people’s lives. It will change your life. You’ll become the slacker prince of indie rock and, as befits the title, you’ll never have to work another day in your life. MORE […]

maybe the best piece I’ve ever read on Stephen Malkmus, a man I ought to know better for good reasons, but does anyone really know him? and yeah his dad IS a great guy. anyway I went to the reunion shows in 2010 and in a good way it wiped away everything crummy from the last 10 years, for a while. I saw SM & the Jicks in 2001 and they were solid. thanks for having written this. and I hope the story keeps going and going..